The Promise of Precise Mass

AI will democratize new ways to live — and die.

There is an old joke about billionaires. One of them, let's call him Mr. Lively, was planning to go on vacation at a small Pacific island resort. Six months before his arrival, his team called the resort to ensure everything would be perfect. Given the unlimited budget, the eager resort manager asked detailed questions.

"What kind of sand does Mr. Lively prefer?"

"White as snow," replied the team.

"And the water color?"

"Deep blue."

"Any favorite fruits?"

"He loves oranges."

"And, if I may ask, what would his ideal beach companion look like?"

"Ah yes - tall, middle-aged brunettes, preferably with glasses."

Over the next months, the island underwent a complete transformation. Pure white sand was imported from Africa. Special dye was added to the water to achieve the perfect blue. Orange trees were planted with climate control systems to survive the tropical weather. And several elegant middle-aged brunettes were recruited to populate the beach.

Finally, Mr. Lively arrived and had a wonderful time. On his last day, he sat on the beach next to a bespectacled brunette, eating an orange and admiring the view. He picked up a handful of pristine white sand, gazed at the deep blue sea, and said with satisfaction: "You see, darling, there are some things that money just can't buy!"

In the past, you had to be a billionaire to enjoy such a personalized experience. The history of industrial capitalism can be seen as a journey from delivering things en masse to delivering them on a personalized basis. At first, people had little. Then, they all got the same mass-produced stuff. Then, as disposable income grew, people started yearning again for things that were boutique or organic or custom. The market obliged, enabling more people to access things that "nobody else had." This made people feel different, but they were still "different, like everyone else."

New boutique products like organic breakfast cereal or cruelty-free makeup were nice, but they were still mass-produced. Still, giving people more options was a big step forward. It achieved two important objectives: It enabled more people to have their needs met more precisely, and it enabled more people to express themselves through consumption. When you buy "fair trade chocolate," you're not buying it for the taste; you're buying it to define who you are.

But capitalism is powered by disappointment. As Jeff Bezos put it, "Customers are always beautifully, wonderfully dissatisfied." People always want more. Buying products and experiences that are exclusive to a smaller group is nice. But you know what's even nicer? Products and experiences that are exclusive only to you — that address your own unique needs and express your own singular personality.

In the early 21st Century, Bezos and others started experimenting with delivering that. Visiting Amazon.com in the early 2000s was less fun than visiting an actual bookstore. But Amazon had one huge advantage: It welcomed you with personalized recommendations. The website had the intelligence to tell you which books you're likely to enjoy, and it had the scale to deliver a wider variety of books than any bookstore on earth.

Soon enough, the web became even more personalized. The "Web 2.0" revolution introduced dynamic websites that showed each visitor different images and texts (and ads). But these images and ads were still chosen from some central repository; they were not really for you; they were just the more relevant options out of a limited number of premade variations. Back then, two people visiting Google News would see completely different headlines, but the headlines were still chosen from a repository of actual stories that happened that day. Two people visiting Facebook.com would see different feeds, but the contents of the feed were still made of posts made by the people in their social network, only in a different order.

The rise of generative AI opened up new possibilities. Today, the boundary between mass and personal is blurring. It is possible to produce giant systems that deliver a different product to every person. Consider three recent announcements from Google, ElevenLabs, and OpenAI. Google is now able to generate realistic videos in near-real time. This means that two people playing the same computer game can see something completely different — not just different angles of the same pre-made virtual world, but two worlds that were generated from scratch specifically for them. ElevenLabs and OpenAI can generate conversations with the same speed, enabling each person to have a different conversation with virtual entities.

Here's Google Veo 2:

And Here's Elevenlabt Flash 2.5:

And here's OpenAI's new 1-800-ChatGPT number:

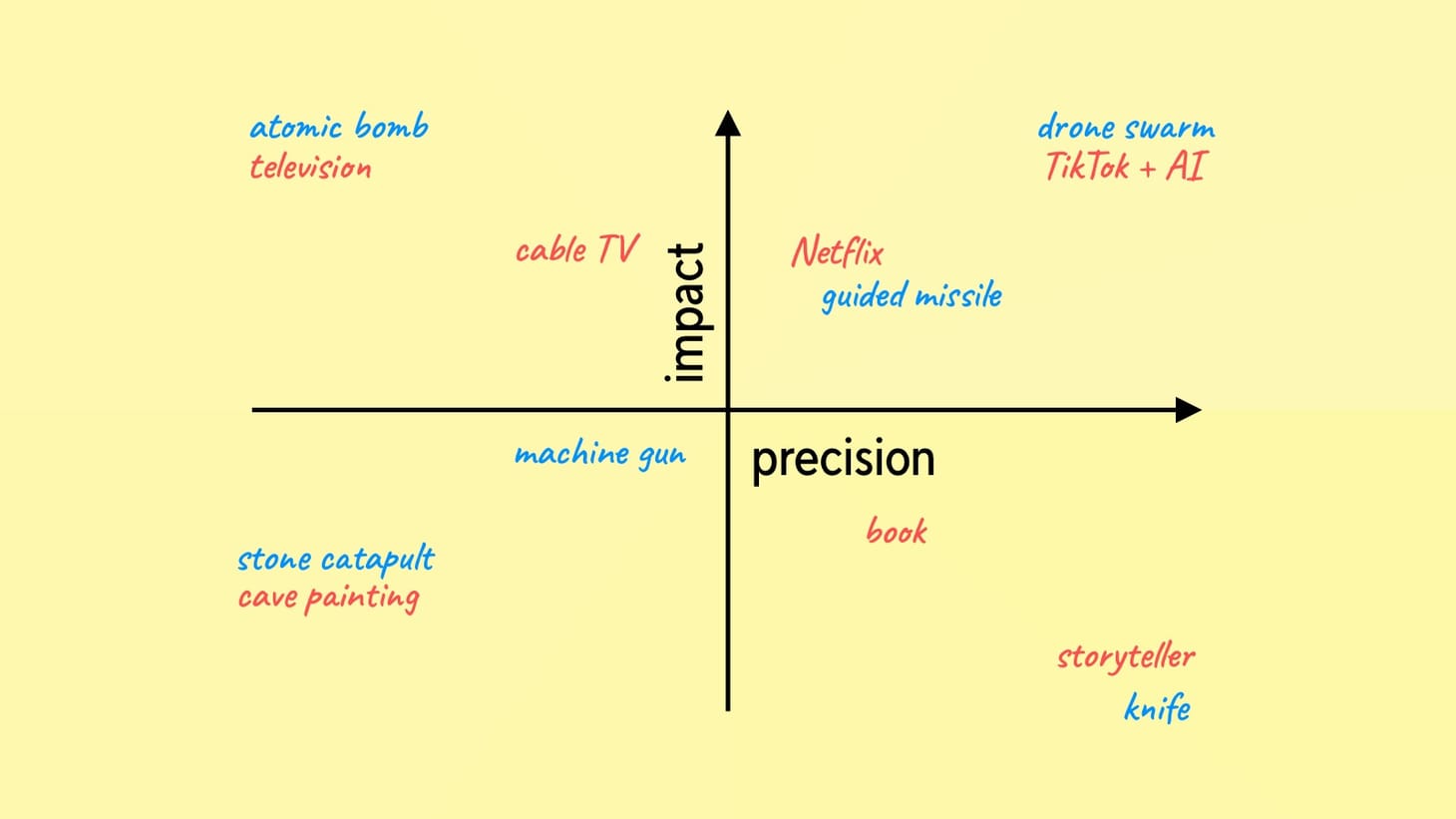

The evolution of media has reached an important milestone. It began with true mass: In the 1950s, America had only a couple of TV channels that broadcast the same things at the same time. Then came cable TV, which gave people more options out of a preset number of channels. Then came Netflix, enabling people to choose both what and when to watch and providing great recommendations on what to watch next. Then came the algorithmic feeds of TikTok and Instagram, automatically feeding people what they are most likely to engage with, out of billions of user-generated videos. And now comes generative AI, creating a new video for each viewer.

Warfare went through a similar evolution. We figured out a way to kill people en masse, culminating with the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Then, we developed precise and expensive "smart bombs" that could hit a limited number of targets. And now we have swarms of drones that are both cheap and precise. Now, we have the mass of atomic bombs coupled with the precision of the assassin's knife: We can hit a thousand targets at once, but hit each of them personally.

The military analyst Michael Horowitz summed it up in a recent article for Foreign Affairs:

The current age of warfare is collapsing the binary between mass and precision, scale and sophistication. Call it the age of “precise mass.” Militaries find themselves in a new era in which more and more actors can muster uncrewed systems and missiles and gain access to inexpensive satellites and cutting-edge commercially available technology. With these tools, they can more easily conduct surveillance and stage accurate and devastating attacks.

Weapons of precise mass are already shaping conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East. Earlier this year, Iran launched hundreds of killer drones toward Israel; Russia is using similar Iranian-made drones in Ukraine. Iran-backed Houthis in Yemen used such drones to blow up Saudi oil infrastructure in 2019, showing how relatively cheap technology can eschew some of the best-guarded facilities in the world. Unlike Saudi, Israel was able to deflect most of Iran's drones, but doing so was costly. As Horowitz points out:

One report suggests the [Iranian] strike cost about $80 million to launch but $1 billion to defend against. A wealthy country and its allies could afford that sort of expense a few times—but maybe not 20 times, 30 times, or 100 times. Fending off this form of attack is not only expensive but also difficult. An assailant can strike at an adversary with a variety of systems; that adversary may be able to repel one specific system but struggle to deal with others.

This basic asymmetry is concerning. And the U.S. and its allies are already working on their own "weapons of precise mass," combining cutting-edge intelligence with relatively cheap unit costs. America's allies are also working on new defense systems that can economically repel cheap, intelligent weapons.

The move towards precise mass, in both entertainment and war, is a key dynamic that will affect all businesses. As I mentioned in a recent chat with Prakash Narayanan:

What artificial intelligence seems to promise is this notion of personalization at scale. Even on the battlefield people are talking about these "weapons of precise mass." You can throw it over a whole area, but it still can make decisions one by one: look at someone's eyes and decide whether they have to die or not. And I find it a really useful way of thinking about it: applying "weapons of precise mass" into every industry and trying to think: "What does that mean when I can deploy something at scale, but also something that is able to make individual decisions within that scale at a super granular level?"

So, what does all this mean for your business or career? What can you do with the ability to deliver something personal en masse? And how can potential competitors use cheap, intelligent "agents" to disrupt your existing business?

I would love to hear your thoughts. Have a great weekend.

Best,

🎤 Are you looking for a keynote speaker for your next event, corporate offsite, or investor meeting? There is a lot going on: AI and distributed work are reshaping our cities, companies, and careers. Are you informed? Are you prepared?

Every year, every year, I inform and inspire thousands of executives across the world in a fun, accessible, and actionable way. Visit my speaker profile to learn more and get in touch with my agent.

Old/New by Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.