The Long Chin

Your job must be performed in person? That will not save you from online competition. New data on the Long Tail offers some evidence.

Studying the internet’s impact on music offers lessons for all other industries. As Will Page, the former chief economist at Spotify, points out, “Music was the first to suffer, and the first to recover, from the forces of deep technological disruption, making it something we can all learn from.”

Two years before Spotify was founded, Chris Anderson came up with a theory to explain how the internet is changing how people consume music and how that theory will ultimately apply to many other products and services.

Before the commercial internet, economic activity revolved around mass-marketing of mass-manufactured goods. It was much cheaper to produce and market large quantities of the same thing. Anderson predicted The internet would change this equation. Digital channels make it possible to send a unique message or show a personalized page for every individual consumer. And they make it possible to store and distribute an infinite number of digital goods (songs, videos) for almost no cost.

The fledgling online music industry offered a case in point. A typical offline music store could only stock around 40,000 songs, while an online service like Rhapsody offered about 500,000. To be profitable, offline stores sell large quantities of a relatively small number of “hit” albums. But online streaming services could sell small amounts of many different songs and still make money.

As Anderson put it:

“Forget squeezing millions from a few megahits at the top of the charts. The future of entertainment is in the millions of niche markets at the shallow end of the bitstream.”

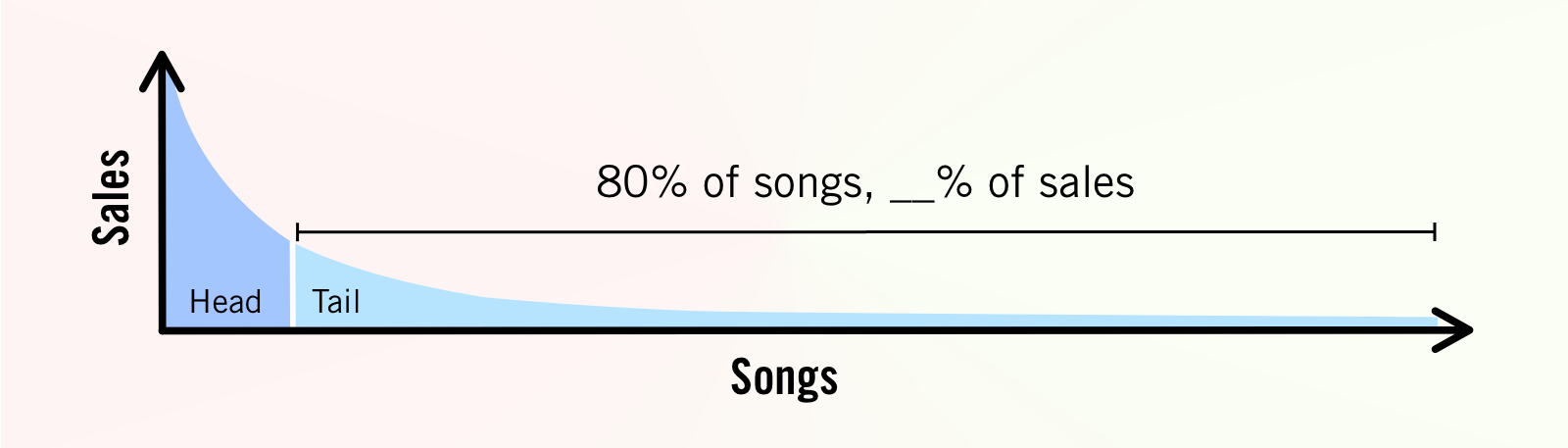

To illustrate his point, Anderson drew a chart plotting the number of unique songs and the number of sales (or paid streams) they generated. Before the internet, 20% of the songs generated about 80% of all sales. This made sense because most music stores could only stock 10% of all available songs.

In the chart, the top 20% of songs are part of the “head” of the distribution, and the remaining 80% are part of the “tail.”

But on the internet, Anderson noticed that things worked very differently. Rhapsody’s streaming service could stock close to 100% of all available songs. It enabled customers to buy 460,000 songs that were not usually available in offline stores. These are the songs from the “tail.” They are not “hits,” but there are many of them. If each of the songs in the tail generated only a few sales, the total number would be huge.

And if the tail could generate a lot more sales than before, the balance of power between the head and the tail would change. The tail could suddenly generate 50% or even 80% of all sales, meaning that “hits” were no longer as important as before.

Anderson called this phenomenon “The Long Tail.” His theory and initial observations pointed to the democratic nature of the internet: the 80% of artists that were previously ignored could gain a higher share of the industry’s revenue, and the power of the top 20% will diminish.

It was an inspiring vision. But things turned out differently.

The Long Chin

Sixteen years after Anderson published his initial theory, music streaming is a giant industry. Spotify and Apple Music customers can access more than 70 million songs, a hundred times the number offered by Rhapsody back in 2004.

Is this the democratic triumph Anderson had in mind?

Not exactly. As Will Page points out in his new book, 88% of all streaming on Spotify and Apple Music is generated by the 40,000 most popular albums. Assuming ten songs per album, this means that the top 400,000 songs generate nearly 90% of all music sales. The “head” is more important than it has ever been.

Was Anderson wrong?

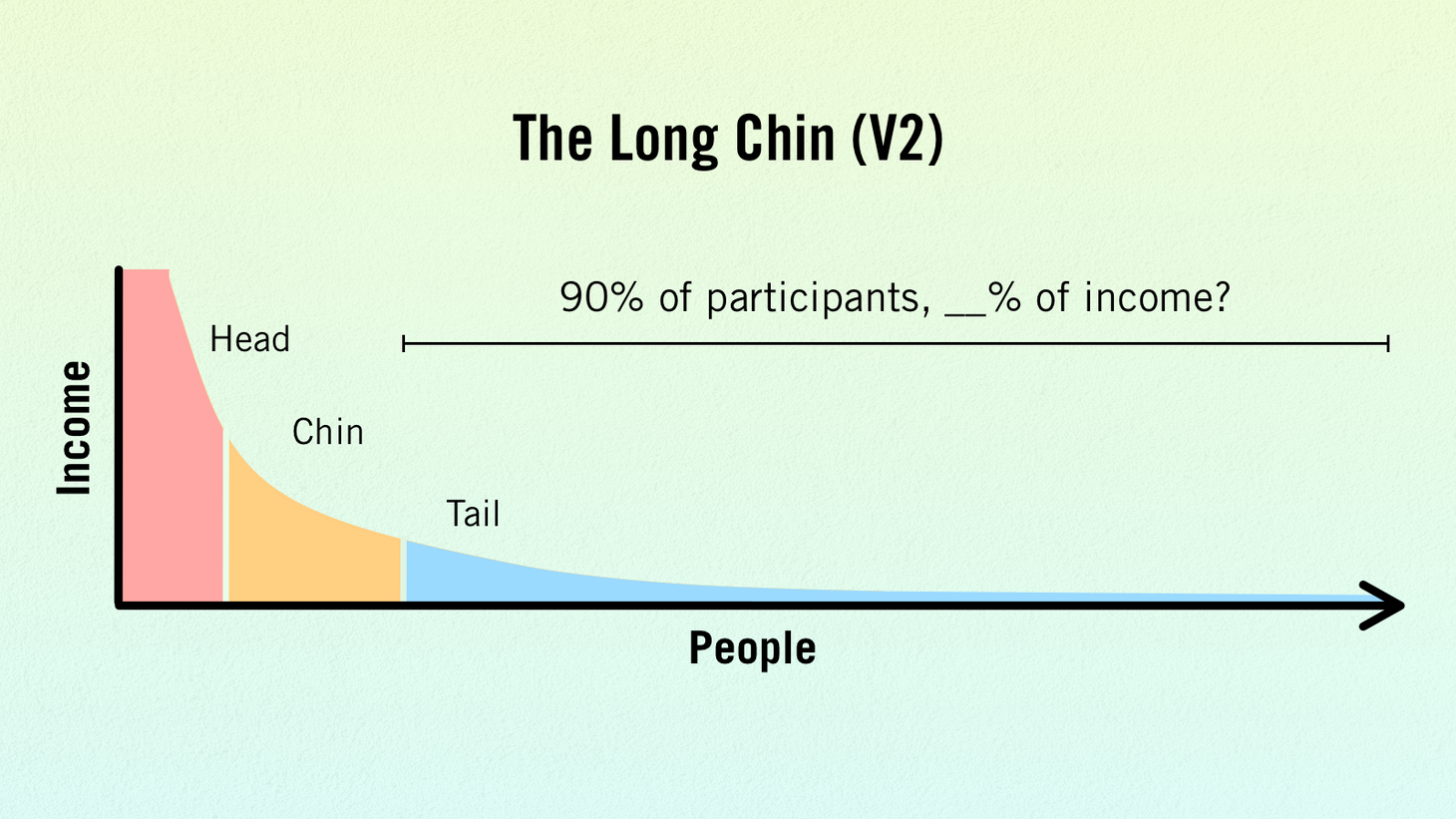

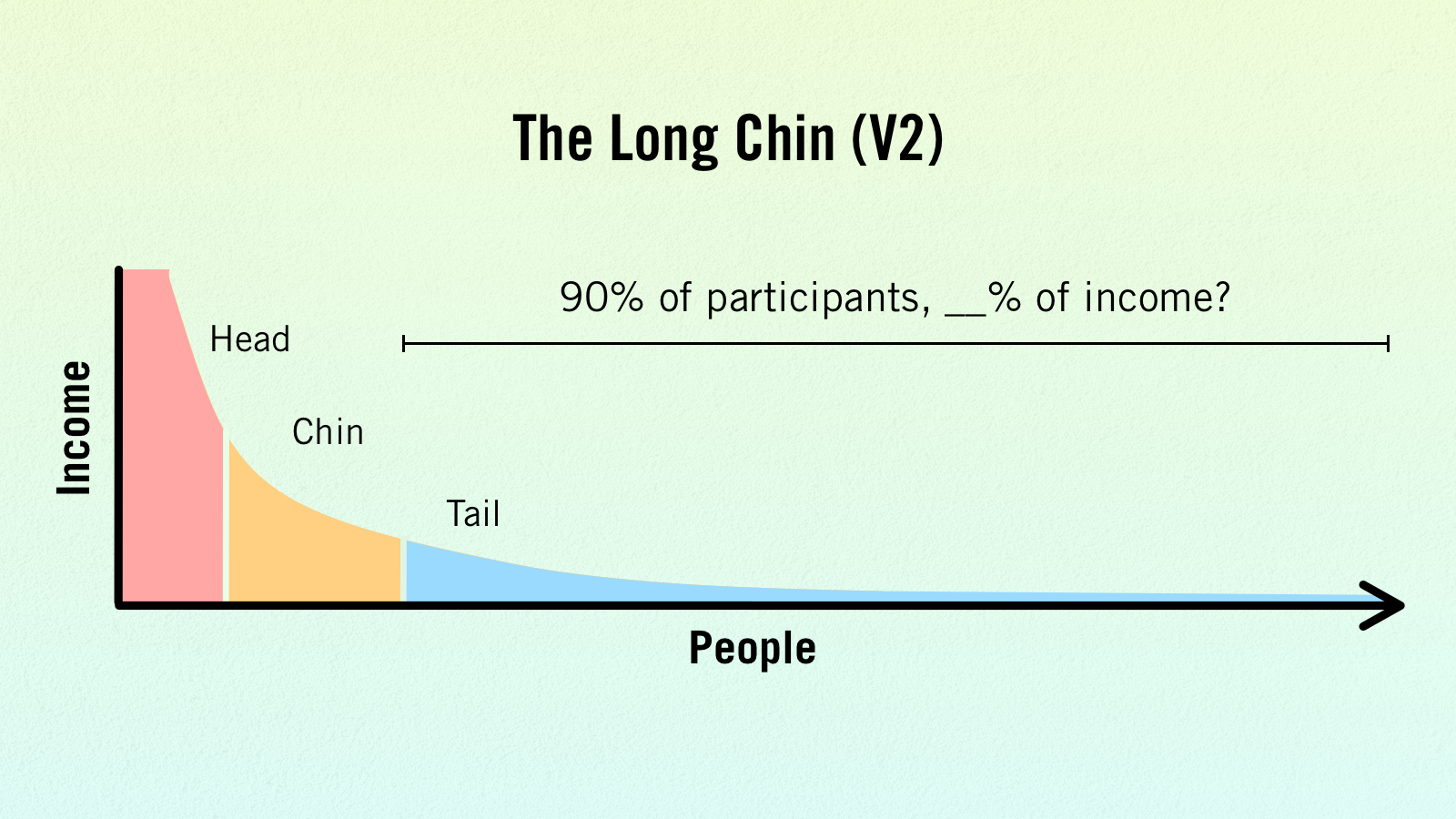

It depends on how you look at it. In percentage terms, the “tail” is still generating 80% or less of all sales. But in absolute terms, the “head” now includes ten times more songs than in 2004. Many more songs and artists are making money from selling or streaming music. But the income distribution among musicians is still heavily skewed towards the top 20%. I call this phenomenon “The Long Chin” — instead of the tail becoming longer, that head is becoming taller.

This is not just a matter of semantics. It has significant implications for the distribution of income from any other products or services delivered online — including remote work. We’ll get to these in a minute, but first, we need to address two questions.

Growing the Pie

If customers can finally access any songs they like, how can a relatively small percentage of songs remain so dominant?

There is no definitive answer to this question, but there are a few possibilities, and probably a combination thereof:

- Streaming services rely on algorithms that recommend songs that users are likely to enjoy. These algorithms tend to favor songs that are already popular.

- Streaming created a giant global market for music, which encouraged record labels to make massive investments in artists with the potential to succeed ( John Seabrooks’s The Song Machine provides a detailed look at how this works)

- Social media, where many people share and discover content, has its own algorithms that tend to promote posts that are already popular. In addition, social media also incentivizes people to narrow their tastes. As John Seabrook suggested to me, “who you are on social media has a lot to do with the music you identify with, and you want music other people can identify with, so you don't need so many choices.” In other words, in a world driven by likes, most people are more likely to share content that they think other people will like.

- Technology doesn’t just make it easier to sell music; it also makes it easier to create music. As a result, many more songs are created, but most of them are not likely to appeal to anyone.

That last point brings up a second and more important question.

Lowering the Bar

Forty thousand new tracks are added to Spotify every single day. That’s more than than the total number of songs stocked in a typical record store. And it adds up to close to 15 million new songs per year. Who is creating all this music? Where did all the new musicians come from?

One possibility is that existing musicians that previously relied on live performances in small local venues are now uploading their songs online. They are doing so for several interrelated reasons:

- They have fewer opportunities to perform offline. Small local venues are shutting down due to competition from online streaming and giant venues.

- The growth of giant venues is driven by the fact that the most famous artists are increasingly reliant on live performances. Locals now have to compete with international stars both online and offline.

- Online popularity drives ticket sales for offline gigs. More than half of offline ticket buyers buy tickets to shows by artists they discovered online. Local artists need an online presence to earn money offline. And they are at a disadvantage competing for offline ticket sales with superstars that have millions of online listeners and followers.

But the bulk of new music is probably not created by existing performers who are “moving” online. Most of it is probably created by people who were previously not performing or recording at all. Technology does not just make it easier to sell and distribute music. It also makes it easier to create it and to learn how to create it.

As a result, many more people are creating music and trying to make money from it. Most of them do not expect to make any money, and most will indeed not make any money. But they create more competition for existing artists — especially those in the “tail,” that wasn’t doing too well, to begin with.

These dynamics are not limited to the music industry.

Facing the Music

Many other performers and professionals can no longer rely on a local venue (or office) to make a living. They are forced to compete with superstars that can perform the same job from anywhere. Even for jobs that must be conducted in-person, locals increasingly compete with other locals that have an online presence that attracts customers (a newsletter, a Twitter/Instagram/Tiktok feed). And they’re also competing with masses of amateurs who have little to lose by crowding the market.

The critical point is that everyone is forced to participate in the same online market to be part of the same income distribution chart. And that the income distribution chart for many professions will become more like music’s, with a small “head” that captures the majority of the profits. As I wrote in No Floor, No Ceiling, we are all in one giant global arena. We can win world-scale prizes. But we have to play — music, or anything else.

The good news is that the “head” has room for more people than ever. It has a long chin that can accommodate hundreds of thousands of new superstars in a variety of professions.

Have a great weekend. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please share it with a friend. 🙏

P.S.

Earlier pieces that explored the The Long Tail and its implications to jobs and cities:

- Living on the Tail: The distribution of people in offices, homes, and cities will be governed by the rules of the online world. The consequences are disturbing.

- The Rise of the 10X Class: The "robber barons" of the 21st Century are the people who used to sit next to you at the office.

- The Office Won't Budge: Real estate is still a zero-sum game. But only for landlords.

Old/New by Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.