Remote Work: An American Problem?

Last week, I wrote about in-person meetings' importance (or lack thereof). I provided some data on the emptiness of American offices, particularly in New York and San Francisco. Some of the comments on that piece highlighted that offices in Europe and Asia are doing much better.

I speculated about possible reasons for the difference in office occupancy between countries. I assumed the situation in New York and San Francisco is worse for several reasons:

- NYC and SF rely heavily on commuters and are less walkable than their European counterparts;

- The commuting experience in NYC and SF is far worse than in many European and Asian cities due to limited or sub-standard public transport;

- The economies of NYC and SF are more dynamic and more dependent on top talent than any city in Europe (with London, perhaps, being on par); an

- NYC and SF have a unique layer of hundreds of thousands of very high earners that have the power to force their flexible/remote work preference on employers.

As a result of the above, people are more reluctant to commute, they are more likely to stay home even when they're told to come to the office, and there are enough such people to impact the city as a whole (as opposed to, say, a minority).

Last month, I also wrote about Apple's planned return to the office and why it will not happen. This week, Apple's CEO acknowledged as much. At the Time 100 event, Cook said that Apple is "running the mother of all experiments" with remote work. He added that "Apple would be the first to admit that 'we don't know' what the hybrid working world could end up looking like" and that Apple is "trying to find a place that makes the best of both of these worlds." He also conceded that "Apple might be the first to admit that the starting point of its hybrid working policy was wrong and could need tweaking."

Meanwhile, more data is flowing in from other countries. The Financial Times has a fascinating piece about The Great Tokyo Exodus. According to private and government data, "more than 350 companies moved their main offices from Tokyo and its neighboring prefectures to the countryside last year." And in 2021, "more people left Tokyo's central 23 wards than arrived, for the first time since records began."

Over in Ireland, the government just announced new funding for remote working hubs across the country, including vouchers that would give employees free access to nearby workspaces and meetings room. This is part of a broader initiative to encourage the spread of economic activity across the country rather than in a handful of cities. The Irish Government also funds a national database of flexible workspaces. Thank you, Paul Gaughan, for bringing this to my attention.

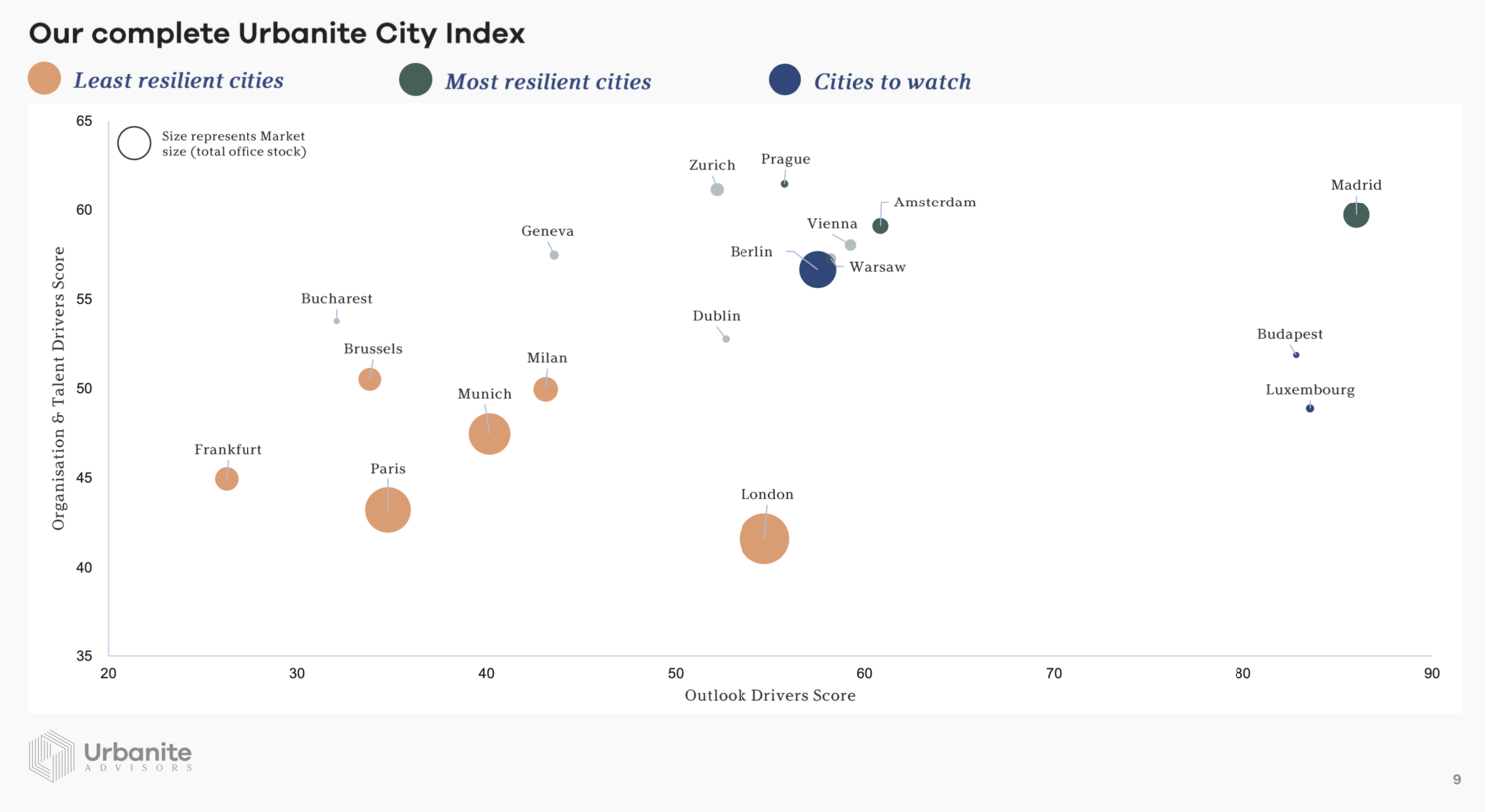

Another reader shared with me an interesting report analyzing remote work's impact on different European cities. The Urbanite City Index ranks European office markets based on their dependence on long commutes, the share of organizations that adopt or are likely to embrace remote work, and other economic characteristics such as projected growth and availability of suitable workspaces.

The index highlights compact, walkable cities such as Prague, Madrid, and Amsterdam as being "most resilient" in the face of remote work. It also highlights the risk to juggernauts like Paris, London, and Frankfurt — cities with strong economies but high dependence on employees with long commutes. These findings align with my predictions that many European cities will do better than American ones since they have pre-industrial urban planning that de-emphasizes automobiles and prioritizes walking and public transport.

Back in New York, Bloomberg reports that more people are moving to Manhattan than before the pandemic. The population is still declining, but the decline is slowing down. Due to the lack of new construction, the slowdown in out-migration is already pushing residential rents to all-time highs. And as the New York Post points out, a lot of the demand comes from remote workers who can live anywhere but choose to live in New York for the lifestyle (but not for the office).

This, too, is not surprising. Last year, I was on a panel with the CEOs of the two leading co-living and co-working operators, Brad Hargreaves of Common and Jamie Hodari of Industrious. My hottest take back then was that while New York City's offices are in trouble, I expect Manhattan's residential population to be higher in 10 years than it was pre-Covid. Cities that offer a great lifestyle will remain attractive. However, they will still have to contend with repurposing many office buildings and reorienting retail to cater to something other than office-based morning and lunch swarms.

Ultimately, As I wrote in the New York Times at the beginning of 2021, changes in the office market "will be gradual, but they will have a significant impact on urban office buildings, which used to be perceived as almost as safe as government bonds." Back then, I compared this process to what happened to retail: the "retail apocalypse" led to multiple bankruptcies, and the closing of tens of thousands of stores "was a result of less than 12 percent of all activity moving online, over a period of two decades, while total sales were still growing."

With office, this will happen faster and to an industry that is far less prepared. And it will happen everywhere, but not with the same intensity.

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.