Let's get physical

The built world holds the key to humanity’s biggest problems, especially when people can live and work anywhere.

Does the physical world still matter? In 2021, this is a contentious question. More people can work, socialize, study, shop, and access essential services from anywhere. The online world enables us to focus only on the things and people that interest us. As such, it is systematically more attractive.

But just when we’re about to abandon physical reality, its appeal is rising. The built world holds the key to humanity’s biggest problems. It is the frontier in which the biggest technological innovations must prove themselves. It is a store for giant pools of institutional money. And it presents a massive business opportunity for entrepreneurs.

Andreessen’s Dilemma

Ten years ago, Marc Andreessen observed that “software is eating the world.” This year, he realized the world might not be worth eating at all:

"reality has had 5,000 years to get good, and is clearly still woefully lacking for most people; I don't think we should wait another 5,000 years to see if it eventually closes the gap. We should build — and we are building — online worlds that make life and work and love wonderful for everyone"

Andreessen, who co-founded Netscape and runs one of the world’s largest VC firms, is protesting the idealization of the physical world. We assume that offline environments are richer, that offline interactions are more meaningful, that what happens offline is, by default, more substantial. But that’s not the case for most people.

“A small percent of people live in a real-world environment that is rich, even overflowing, with glorious substance, beautiful settings, plentiful stimulation, and many fascinating people to talk to, and to work with, and to date…. Everyone else, the vast majority of humanity, lacks Reality Privilege — their online world is, or will be, immeasurably richer and more fulfilling than most of the physical and social environment around them in the quote-unquote real world.”

The idea of “Reality Privilege” is interesting. Indeed, it might be better to spend your days walking (and working) around London or Tokyo or Bali or Chiang Mai than on Twitter or Fortnite. But most people don’t live in a magnificent city or an exotic remote hub.

When comparing the real world to its online alternatives, we need to consider how and where most people actually live. For most, the physical world means environmental degradation, substandard or non-existent infrastructure, violence, and crime. The physical world is also a source of more mundane inconveniences: long commutes, awkward silences, the constant reminders that we ourselves are physical and mortal. As agent Smith tells Neo in The Matrix:

“I hate this place. This zoo. This prison. This reality, whatever you want to call it, I can't stand it any longer. It's the smell….”

Making the real world rich, pleasant, and safe for most people is a giant undertaking. It’s barely possible. And since it’s much easier to build a nicer online world than to fix the offline one, why bother? As Ross Douthat asked last week in Andreessen's Dilemma:

"if virtual reality is destined to be better… then shouldn’t we want all our best minds even more focused on its possibilities than they are today?”

The answer is no. There are social, environmental, financial, and even spiritual reasons to attempt the impossible. Our best minds should focus on that.

A Personal Dilemma

Choosing between the online and offline world is something I’ve personally struggled with for many years. I started my career with one foot in each of these worlds — designing websites and writing online about offline music events and parties. Later, I ran a digital design agency, but most of my clients were offline companies — retailers, hotel chains, real estate developers. One of these developers recruited me, and I spent a decade building things — malls, apartments, offices.

Building physical shopping malls in China, I was forced to keep up with the online world. Many of the marketing, sales, delivery methods that brands are now adopting in the West were par for the course in China more than a decade ago. I worked in real estate but spent a lot of time with online retailers, mobile payment providers, and anyone who had something new or unusual to share.

In parallel, I was writing online at now-defunct websites such as Danwei and BuyBuyChina, analyzing emerging technologies and consumer behaviors. I advised several startups trying to integrate digital and physical commerce — most notably Tango, an early unicorn that received $215 million from Alibaba to experiment with merging chat, video streaming, gaming, mobile payments, and offline retailers.

Ultimately, I tried to escape the real estate world completely and founded my own startup, launching an app that made it easy for people to discover events and interesting conversations within walking distance. That app led me to New York. It also led me to realize that running a startup is tough, that I enjoy writing more than anything else, and that it’s impossible to escape the physical world. The people who were most interested in the app were operators of actual buildings — coworking spaces, music venues, multifamily projects, university campuses, shopping malls, business improvement districts.

The app died, but my interest in bridging the online and offline worlds persisted. So I decided to take some time off and write about it. The result was Rethinking Real Estate. The book was completed in 2019, but it predicted a lot of the turmoil we’re seeing in the world of offices and housing in 2020 and provides a roadmap on how to navigate 2021 and beyond.

But even though I am a so-called real estate expert, I still struggle to belong to this industry. I am fundamentally an online media guy. Most of my time is spent researching the two “edges” of the built world: On one side, people’s behaviors, and on the other side, the financial implications of these behaviors.

I am far less interested in the buildings themselves, in how they are made and operated. But I force myself to study that as well. I force myself because I know that without the buildings, nothing else is possible. And that the supply, quality, cost, and usage of physical structures have an immeasurable impact on everything. How the built world is made, operated, and financed is inextricable from the most critical challenges we face: climate change, income inequality, racial segregation, mass migrations, loneliness, obesity, and even political polarization.

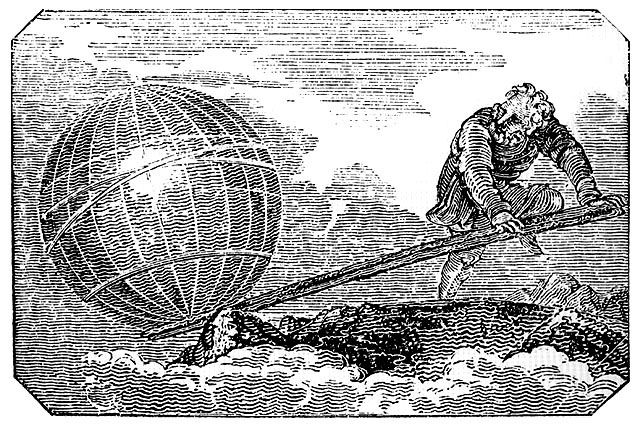

Two thousand two hundred years ago, Archimedes realized that if you have a “solid place to stand on, and a lever long enough,” you can move the world. Real estate is that solid place. Innovation is a lever. Applying it to the built world will significantly impact our society and planet over the following decades.

More importantly, a failure to apply innovation to the built world will undermine anything else we manage to achieve. Humans need to breathe, they need to eat, they need to move around, they need to interact with each other, they need to be safe from physical danger. Their ability to do all these things depends on the quality of their physical environment. VR goggles, immersive games, and live-streamed kisses cannot make up for physical decay.

The Long and Short Road

The Talmud relates a story from a Rabbi who lived 1900 years ago in the Galilee:

“One time, I was walking along the path, and I saw a young boy sitting at the crossroads. And I said to him: On which path shall we walk in order to get to the city?

He said to me: This path is short and long, and that path is long and short. I walked on the path that was short and long. When I approached the city, I found that gardens and orchards surrounded it, and I did not know the trails leading through them...”

The short road went in the right direction but led to a dead end. Focusing only on the digital world is that short road. It is tempting, it even seems rational, but it will not get us there.

The ability to live and work anywhere introduces unprecedented dynamism and urgency to places and industries that have resisted change for far too long. We need more of humanity’s best and brightest to apply themselves to these places and industries. There are significant problems to solve, there is plenty of money available, and landlords and cities are finally open to new ideas.

Next week, we are launching a new cohort of Future-Proof Office and Future-Proof Housing. Our courses and community give participants the context, contacts, and confidence to reshape the built world. We have 400+ alumni from 35 countries and five continents — entrepreneurs, investors, designers, builders, operators, government officials, academics — all focused on making cities, offices, and homes better. Join us!

And have a great weekend.

Old/New by Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.