Judy Stephenson on The History of Working from Home

Earlier this week, I hosted Dr. Judy Stephenson for a chat about the history of working from home and mixed-use cities. You can watch the whole thing below or listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and beyond.

Judy Stephenson is an Associate Professor at University College London, specializing in the history of labor markets and the built environment. In addition, Judy is a research associate at both the Oxford Centre for Economic and Social History and The Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure, and a Director at the Long Run Institute. Her insights have been featured by The Economist, Financial Times, and beyond.

Judy’s upcoming book, Wages before Machines, explores salaries and bargaining in the pre-industrial world. Follow her on Twitter @JudyZara.

Transcript

[00:00:18] Dror Poleg: Today I have a very important guest, my friend, Dr. Judy Stephenson. She's an associate professor at University College London. She's a research associate at Oxford University and Cambridge University. She's a director of the Long Run Institute. And generally writes about the history of labor markets and the relationship with the built environment. Her insights have been featured in The Economist, the Financial Times and Beyond, and she's currently working on a book about salaries and wages, and before the rise of machines and automations.

[00:01:03] Dror Poleg: Judy, after this elaborate introduction, welcome. Great to see you!

[00:01:07] Judy Stephenson: Thank you very much for having me. It's lovely to see you and talk.

[00:01:11] Dror Poleg: And I think the last time we got to a chat in public was in class probably like 12 or years.

[00:01:16] Judy Stephenson: Yeah. Probably 12 or 13 years ago at LSE. Absolutely. Yeah, a taster for anyone who yeah.

[00:01:22] Judy Stephenson: Wants to know what economic history at LSE is. It produces people like

[00:01:26] Dror Poleg: us. Yeah. Yes. For better or worse. So let's jump back. 300 years. So let's start with London. So viewed from above, what did urban work look

[00:01:35] Judy Stephenson: like? Okay, so I'm gonna take you to like the late 17th, early 18th century in London.

[00:01:41] Judy Stephenson: And so let's pretend we're talking about the period just after, within a sort of decade or 20 years after the Great Fire of London where the city is already rebuilt and starts growing very rapidly. So we're talking boom time, 17th century boom time. Urban work really in this.

[00:01:57] Judy Stephenson: In London all looks all about the services sector. There are, there is product. , know, people are making things. There's crafts. , people making very high end goods, particularly anything of high value will be made in

[00:02:07] Dror Poleg: workshops. What kind of goods and what kind of services are we talking about?

[00:02:11] Judy Stephenson: Oh, everything. There's, I this is the cornucopia of wonderful new goods. This is nearer of new goods. Furniture ceramics glass. There's glass makers in London. The Murano makers move here in the 17th century. Because England has a particular approach to crystal and glass making that becomes very important in the 18th century.

[00:02:29] Judy Stephenson: Sugar the sugar bakers have, these have warehouses with these big copper pots and sort of min seeping over them building construction. The construction accounts for well over 10% of the economy, most of this time. Gold clothing, glove, and anything that can be consumed is being maybe not made but assembled in London and sold in London.

[00:02:49] Judy Stephenson: There's a retail environment all along cheap side, growing into the West End. So there are skilled people making things. The unskilled people are moving stuff around. . So they're digging . . And they're messy and they're moving stuff like they're moving earth, they're moving people, they're on the river.

[00:03:07] Judy Stephenson: A lot of river stuff. On the river. There's a lot of activity around the bridge. They're moving stuff in the markets. Around the markets. They're moving things through the streets. They're also moving information. You've got lots of watchmen and messengers who are basically running around with little message.

[00:03:20] Judy Stephenson: And bills and things all over the city. Apparently the traffic is much worse than today. It takes two hours to cross London Bridge at some point in this period. And that's by

[00:03:29] Dror Poleg: foot. So where are they running? Where is most work producer people in offices, in factories?

[00:03:34] Dror Poleg: Wh where is the workplace? What does the

[00:03:36] Judy Stephenson: workplace look like? That's a good question. The workplace is the city in a sense the conception that we have of a workplace. Like an office to, or a manufactory to do with a particular employer that's, yeah. That's not quite the same.

[00:03:52] Judy Stephenson: To understand the conception of what a workplace is, there are workshops and sellers of goods where some people come to work, but most of the people who would have. with that place or with that, that trader don't necessarily work in the same place. , it's only, it's only the apprentices and the very, very, most people don't have a full-time job.

[00:04:13] Judy Stephenson: They just have occasional work. Particularly the unskilled tend to be out and about. They're outside in markets, moving things around. They're on the river or they are moving. , warehouses and sites people who do have, are beginning to have what we conceive of as an office are in administrative roles and they have positions.

[00:04:31] Judy Stephenson: And, but even like Sam Pepys, Samuel Pepys, who was the most famous Londoner of this period,

[00:04:35] Dror Poleg: Because he wrote a diary that everyone still refers to. Yeah, that's

[00:04:38] Judy Stephenson: absolutely, yeah. know, It. It's very naughty. But his life is getting out and about. He's, he's got a major position on the Navy board.

[00:04:45] Judy Stephenson: He's a, he's se he's a secretary of the admiralty. And he, his life is going out and about and meeting people in coffee houses and meeting people in other administrative offices, but he doesn't have a desk he goes to every day. And he works bizarre hours, crazy hours,

[00:04:59] Dror Poleg: wherever. So that's like a typical, if we're zooming in into one type of person.

[00:05:03] Dror Poleg: What does a typical day look like For a merchant or a position holder?

[00:05:07] Judy Stephenson: Yeah the it, it consists of meetings or, yeah. A lot of meetings that one has to have

[00:05:13] Dror Poleg: But the meetings happen where, ,

[00:05:14] Judy Stephenson: They happen in people's houses. So merchants particularly do have a workplace.

[00:05:19] Judy Stephenson: And this is a, as a, they have the, and it's a combination of the family home, which is, about. And that was where you would have meetings if you like. These are about intimacy. This is a tradition that carries on, particularly in banking right up know, the 20th century in the big banking houses.

[00:05:34] Judy Stephenson: But you also then have a place of counting. Accounting house. And you also then have a place where stuff is stored, inventory stored. So there are,

[00:05:42] Dror Poleg: three or four. So the office is at home, it's like a townhouse of some sort, where you have your meetings. Then there's a separate place where.

[00:05:50] Dror Poleg: Clerks sit, but not hundreds of them.

[00:05:53] Judy Stephenson: gathers come later. Clerks come much later. So if you look at so let's take a 17th Century bank, one of the first whores, which still have offices on Fleet Street, pretty much in the same place there. The structure of the building at the time were offices where the senior bankers could, the people actually taking deposits and working out the risk and saying we land.

[00:06:12] Judy Stephenson: Would work, would be, but the work of the Clarks and the record keepers was done elsewhere. And it's literally just a book with a place to write. It's not that those people don't have a workspace, as it were. . And the tradition, certainly within the church and within bigger organizations is that there are, there's a desk or a place where the book is, but that's not necessarily your workplace except for the, you the very cons.

[00:06:37] Judy Stephenson: sacred Monks. So in the late 17th, early, say 18th century the notion of a workplace our notion of a workplace is confounded by two things in that area. First of all, most people don't work for the same employer all the time. Like the job. Nobody really has a job. People have bits of work.

[00:06:54] Judy Stephenson: They have some work that they're doing right now and they might be working for somebody else in a few months time. And the place, they're more likely to be moving around between places that things have to be exchanged than actually in one place. So the whole city is a buzz the whole time.

[00:07:08] Judy Stephenson: . But the notion of having, a desk. and something that you come into every day is much more modern than. .

[00:07:16] Dror Poleg: So it's more of an idealized, capitalist world that kind of, Adam Smith wrote about before we started thinking about firms and offices of yeah. The, a price coordination mechanism sends people around, whether on a daily basis or monthly basis to just do whatever the economy,

[00:07:31] Judy Stephenson: the market is all around.

[00:07:32] Judy Stephenson: Yes, the market is all around you, and I think it's important to say that people are not being paid, in steady jobs. So when they do get paid, they get paid for. the thing that they sell. , the task that they're a asked to carry out or to to hold a position and take responsibility for a certain thing for a certain amount of time.

[00:07:50] Dror Poleg: So presenteeism is not a big deal in the 17th and 18th century. So what, whatever you produce, you get paid for it. . So we spoke a little bit about like the upper class people, and maybe we can come back to them, but if we wanna zoom in on like a white collar or like a laborer during that period, what does their life look for, look like?

[00:08:08] Dror Poleg: Like what are they doing? Where are they doing it? How are they getting paid

[00:08:11] Judy Stephenson: for it? So laborers in London at the time are either working on construction sites or they're hauling stuff around. and the people who are hauling stuff, they're working on construction sites. They will be working a 12 or 13 hour day with a break in the middle and possibly a break.

[00:08:28] Judy Stephenson: It's so very early, about 6:00 AM right through to, evening, depending on the light. Sometimes it's shorter and winter. And there'll be a break for food in the middle of the day that the, it's their food, nobody's given it to them. And it's basically hard graft, the life of a laborer.

[00:08:43] Judy Stephenson: Men die early for a reason in that, you're working brutal physical hard labor all day on, on the river. What you're doing is you're hauling stuff from a from place to place. And because you're paid for the task, not for your time when you're hauling you basically ha there's a lot of hanging around on the river looking for things moving stuff on lighters, which are small, the small boats that go.

[00:09:04] Judy Stephenson: The larger boats in the shore and that go between the larger boats and through under London Bridge and up to the different steps. You might be working for six or seven employers in a day. , so

[00:09:13] Dror Poleg: like an Uber, like the Uber drivers of the river, basically. The

[00:09:17] Judy Stephenson: Uber drivers the same thing. And the city, that turns into quite a tough market and the city regulates it.

[00:09:21] Judy Stephenson: It says there's this much, these are the. that can be paid for waterman, enlightenment and Holls. And this is how they're gonna pick up tickets for those things and everybody has to be registered and do all that kinda stuff. So that gets regulated early. The time, the, in terms of that also work is really seasonal.

[00:09:37] Judy Stephenson: . So nobody, the time of year that we are now, early March work is just picking up again because in early Martin London in service. People don't do much in January and February. It's called Candlemas. There's this all work records show people working really hard up to December 25th and then January, February there's a few people flicking stuff around.

[00:09:56] Judy Stephenson: And then in March, work picks up again before the big accounting day, which is lady day 25th.

[00:10:02] Dror Poleg: So just to summarize where we are until now. So we're looking at a city. As you said, like the workplace is the city or the city is the office as some say these days people are mostly unaffiliated with large organizations.

[00:10:14] Dror Poleg: Large organizations largely don't exist so much apart from a handful. And both kind of the upper class and the working class people They tend to work or do business with multiple different employers or partners. Work is generally more piecemeal or contract based rather than just getting paid for your time.

[00:10:32] Dror Poleg: Every spa spatial arrangement in terms of where people work and how cities are designed seems to dictate or at least reflect some kind of economic arrangement. So did the location of these workplaces affect how people were compensated, how many hours they worked, other aspects of their lives?

[00:10:47] Judy Stephenson: Yes. I think it's the other aspects of the lives is I'm talking about apart from hard laboring, I'm talking about both women and. Cuz women particularly are very well represented in the goods market. And so they tend to, own that small, workshop or warehouse and people come in, they have apprentices, they have servants.

[00:11:05] Judy Stephenson: The children are living out, with nurses or other family or are in an apprentice. But there's, there's servant. and other people may be in, and these are the people who are in a workplace, by the way, as domestic servants. Both those who come in with the aristocracy for the season and those who are also attached to households and houses.

[00:11:23] Judy Stephenson: How

[00:11:24] Dror Poleg: are they employed, by the way? So they're like the, maybe an example of an early employee, like the Downton Abbey downstairs.

[00:11:30] Judy Stephenson: Most of that is done on what you call an, so even that contract is very short by today's com job comparisons. , because you sign up for. Okay, so you, so at the end of every year you go, are we doing this again and the contract is we'll pay you this much at the end of the year. And then this is the kind of board and lodging you have. Yes, you're allowed butter, you're not having cheese. Yes, we'll buy you, we'll get you delivery or clothes. You can have an allowance for this or whatever.

[00:11:54] Judy Stephenson: And it totally depends on

[00:11:55] Dror Poleg: the house, but you get paid at the end of the contract. Until then, you're just basically allowed to live and eat.

[00:12:00] Judy Stephenson: And yeah, if there is a cash payment, you get paid at the end of the contract. Absolutely nothing. Nothing in between. Cuz you, you were put up in between. So some live very well if you're part of a nice household, this is great.

[00:12:10] Judy Stephenson: If you're not also great.

[00:12:12] Dror Poleg: I'm trying to negotiate something similar with my wife now just to let me know.

[00:12:15] Judy Stephenson: Indeed. But the other people who are making goods, of course are not because they're working for different people. They are, their incomes are dependent on demand. So obviously they've got very little income in January and.

[00:12:28] Judy Stephenson: then they'll work very hard for maybe other bits of the year. It really depends on what we think of as effective demand, . But they might have a lot of work. And work very long hours, through the nights or subcontract to other people at peak times, and then that would break again. Essentially what this means, the relationship between the kind of workplace and the economic arrangement is the idea of work is very precarious.

[00:12:52] Judy Stephenson: So what we understand, as you've got a job, you paid a salary, you paid for your time. These are not assumptions you can make for early modern workers. Assume that there will be work and an income will come, but who mostly also have to do their own accounting and write their own bell.

[00:13:08] Dror Poleg: Yes. So before my next question, I just wanna remind everyone if you have any questions about the history of work that you wanna throw it, Julie or me, drop them in the comments, whether you're on LinkedIn or YouTube or Twitter, wherever you are. I'm trying to keep track of everything. Let me have a look here just to make sure I didn't miss anything and.

[00:13:26] Dror Poleg: Okay, so moving along. So when and why did this arrangement stop? Like when and why did work move out of the house? Did it happen at once? Did it happen in waves? What happened? So

[00:13:39] Judy Stephenson: how did we end up here, ? How did we end up here exactly. Good point. So two things happened, particularly the end of the 18th century.

[00:13:44] Judy Stephenson: The first is that the manufacturer of goods becomes industrialized and moves away from London. Largely it's. Lingers in London and the other big cities in and workshops, right to the end of the 19th century. But large scale employment moves outta cities and into manufacturing factories and the experiments

[00:14:03] Dror Poleg: and how the technological trigger, yes, so like steam and later other types of power basically.

[00:14:09] Dror Poleg: Require more people to be around the machines or to move stuff towards the machines. It's generally

[00:14:14] Judy Stephenson: held to be about the energy, about the power, like the source of, the big, and you get, this is why you get sort of tall factories as well. There's a, there's one power source before electrification when you're doing steam.

[00:14:24] Judy Stephenson: There's one power source, one lever and you the machines are basically, into that, which also gives you a limit. , the total number of machines that you can have. But these manufacturers tend to be built outside of cities close to coal and water power. And that creates a a new type of work where obviously then the administrative job of organizing it, accounting for it, paying for it, managing suppliers and all that kinda stuff turns into the white collar.

[00:14:52] Judy Stephenson: of industrialized

[00:14:52] Dror Poleg: businesses and that remains in the city, or it moves out first and then comes back when it has telegraphs or other ways to communicate. It's it's,

[00:14:59] Judy Stephenson: it's, it doesn't really come back into London until the end of the 19th century. Except apart from some like London kept sugar and a couple of other industries, but most industry boom takes off in the northwest of England in what is now Manchester and Lancaster.

[00:15:13] Judy Stephenson: So where the good music is, where the good music is. and they're completely correlated. Absolutely. . That, that turns workplace. And at the same time, because the state starts organizing. Military action, particularly in a much bigger way through the Revolutionary Wars. The lar, the organization of state and its administration gets bigger and that gets EDI to more big offices.

[00:15:35] Judy Stephenson: So Somerset House, which is on the river here, just office at ls, d is, the first, damn, we need some office space. 1775. We need big office space. And that becomes the model for officer. For many big organizations, banks and merchant insurers and all that kind of financial services and other services around there as well.

[00:15:55] Judy Stephenson: And essentially what those early offices are, they're still counters. They're not places where you have desks and cups of tea and, places to hang out and any kind of lifestyle. They are counters where stuff, accounts can be written. And it's only in the mid 19th century that you start to.

[00:16:10] Judy Stephenson: The continuation of Clarks or administrators who are paid for their time, who you can see and oversee. So it's really the oversight of work and firms beginning to manage productivity in the sense of looking at people and managing them. From the early 19th century onwards, that creates what we understand in the modern workplace.

[00:16:29] Judy Stephenson: And this is, by the way,

[00:16:30] Dror Poleg: speaking of tea, I just, I wrote about it last week in the 1910s. There was a very fierce discussion on the pages of the New York Times about whether American offices should adopt. For 4:00 PM tea, just like in England, and a lot of people had very strong opinions about the Brits not really working too hard, and Americans never would never have time to drink tea at 4:00 PM because they're actually hard at work and it's distracting.

[00:16:53] Dror Poleg: And then they did some research and found that people can actually drink tea and work at the same time. , which was a revelation apparently an American business.

[00:17:02] Judy Stephenson: Can you imagine the crisis of etiquette though? Like all this

[00:17:05] Dror Poleg: They could take dictation and sip in parallel. Yes. Yeah.

[00:17:08] Judy Stephenson: So the the urban structure of work around services really only grows in the, from the mid 19th century onwards.

[00:17:16] Dror Poleg: And then what happens? So you mentioned that a lot of manufacturing moves out of the city. Let's say 250 years ago or so, or a little earlier maybe in England. What happens to all of those offices that used to be in houses and to all the places that hosted people working?

[00:17:29] Dror Poleg: Like how are houses being transformed as a

[00:17:32] Judy Stephenson: response to that? So houses are being transformed in the sense that There is a suburbanization is not just a 20th century phenomenon. From the late 18th century. The well-to-do merchants started building pretty villas, a couple of miles from the city center.

[00:17:46] Judy Stephenson: So the fir, the first bit of that is what we now call. , Belgravia and Chelsea. And the subsequent bits of that are what is now zone three of London. The Wimbledon's, the Stratums, the hamsters are the nice places where well-to-do well-healed professional classes, built big villas for easy access to the city.

[00:18:05] Judy Stephenson: So the, there's, that's a sort of first wave of suburbanization which has actually been going through. The early 17th century when the city of London got too crowded and noisy before the fire, and everyone's like, Ugh. Yeah. Too much. So you have this constant cycle of living and working and living and working within the big cities.

[00:18:21] Judy Stephenson: It's New York has the same with its suburbs and those, there's these constant power balances between, but essentially for a period then in the 20th century, professional work moved out of big. . We all moved outta big cities. Big cities, went outta fashion and then went back into fashion in the late 1980s with the globalized financial services and professional services.

[00:18:42] Judy Stephenson: Yeah. But until that, that generally the trend across the 19th century was to build stuff within the city. , for work, and. The model that you have in New York turned into the skyscraper because of the Houston steel and the model that we have in here in the, in, in London, in the uk because of planning and many things to do with the fire and lack of steel.

[00:19:03] Judy Stephenson: And so also , a fresh mover disadvantage. The high-rise thing never got going. So there, there is a A very particular kind of class structure to 19th century buildings. In that there are certain classes of Clark and just administrative workers who, have no access to the real places of power in the building.

[00:19:22] Judy Stephenson: . So places are much more segmented than they would be. Today. There's literally, entrances. Junior staff, entrances for clubs and entrances for the officers and other places as well.

[00:19:33] Dror Poleg: So you mentioned a few times, things came up like wars fires and obviously we are now living on the heels of, an own kind of.

[00:19:41] Dror Poleg: External disaster with Covid and we tend to look at it as, as a trigger for massive changes in the way people live and work. So what are, like looking back 300 years, what are the kind of main disasters or shocks that shaped the kind of relationship between the city and the office and the home and what was their impact?

[00:19:56] Judy Stephenson: Yeah. The great fire is one and the, when London was completely raised in the sixties, six people thought it would never get going. , that's , that's one thing that happens all the time, is they go, it's never gonna work again. The other main crisis are usually financial crises.

[00:20:11] Judy Stephenson: Okay. The financial cri, war and the financial crisis, but for instance the big cri financial crisis of the mid 1860s. The Gurian brother crisis here in the, in, in the UK banking crisis created a number of bankruptcies, which created what we would call redundancies, which created a bit of a real estate crisis which created demolitions, recurs, reus usages.

[00:20:34] Judy Stephenson: So sounds

[00:20:34] Dror Poleg: like 2023.

[00:20:35] Judy Stephenson: Basically sounds like 2023. The other big change for London, of course, was after the second world. Where large parts of the city were raised through, that's destroy. Yeah. And actually rebuilding there took a lot longer than it had in 1660. There's bits, there were bits of London that did not get filled in again until the late seventies, early 1980s.

[00:20:56] Judy Stephenson: And structurally that created a, first of all, it brought residential. It slowed down residential growth until the 1980s. So London didn't have as much of a workforce as it does. Now, but the second thing it does is it it did was it split, it confirmed the split between financial, which is financial services, which had all been, always been in the city, but there had been other things too and other types of services in the West end. And that became even. Solidified after the second World War, whereas before, before that the two had mixed up more.

[00:21:30] Dror Poleg: So wh which again, parallel process, I'd say in North America as well, in terms of like specific industries or specific office work, really becoming seg segregated into specific parts of the city and have their own buildings with their own shape and style.

[00:21:43] Dror Poleg: I wanna leave some time for a question or two from the audience, but. I think between the lines came out a lot of like social issues whether it is safety, inequality, general kind of squa and poverty. What are some policies that help cities address the shortcomings of the kind of the early modern work from home world.

[00:22:02] Dror Poleg: And, both in terms of their positive intended effects or also maybe some unintended. That we can learn from hopefully today as we're heading into a world that sounds so the thing, disturbingly similar.

[00:22:12] Judy Stephenson: So the thing where there's both regulation and investment from a higher force, it's gotta be transportation.

[00:22:18] Judy Stephenson: , that's the thing that change that makes London's workplace. as they establish in a kind of fixed way in the 19th century accessible to what you might call the working class and the partnership. So the railways are all. Private enterprises, but the private public partnership in terms of planning and how those get constructed, which is sometimes disastrous and sometimes brilliant, is absolutely critical to the path dependency of how the city comes together.

[00:22:46] Judy Stephenson: So in terms of like policy having a policy about where those stations go and where they come into and where where the lines. Has really fundamentally affected the long run working practice and housing as well. So in terms of housing, again, regulation from a safety, health and safety, a fire and , living standards point

[00:23:04] Dror Poleg: of view.

[00:23:04] Dror Poleg: The standardizing basically where people should be allowed to live at all.

[00:23:08] Judy Stephenson: services, particularly like the, it's the sewers and the waters, and what used to be the churches, those were seen as vital services. Until the late 19th century.

[00:23:17] Judy Stephenson: It's those things, the zoning of them, the planning of them, which was coordinated by both, private investors and public servants that created. The ability for there to be essentially that the late 19th and 20th century model is little houses, and workers moving around within a particular city.

[00:23:37] Judy Stephenson: Whereas what, what we had come from in the 17th century had been large places. , and not as non self-contained households and cells and houses. , and a sort of interconnectedness. And. I can see in the chat people are going there seems to be something in this that we're looking at again.

[00:23:50] Judy Stephenson: And the real question of the, do we go into the center or are we just buzzing all around? All around is the hot question now,

[00:23:58] Dror Poleg: all right. So I see we're. we're at time, but we're actually, we can continue for a few more minutes. We have a few questions to address here with the audience.

[00:24:07] Dror Poleg: So good question here from George. It's a little long to read, but basically, you described the transition to industrial work. Pretty quickly. Does that feel rapid to people living through it? Did it happen gradually? What would people have noticed changing around them living there at the time?

[00:24:22] Dror Poleg: And what were the things that were more sticky and didn't change quickly enough, or still didn't change at

[00:24:28] Judy Stephenson: all?

[00:24:29] Judy Stephenson: So I think the biggest changes and also the changes where we have biographies and, people's spoken word on this for the first time. Come from, from the early 19th century after the Revolutionary Wars, when the railways are beginning to be laid out.

[00:24:42] Judy Stephenson: And people will say I grew up around here, around more fields or Yeah what is now, and you. , there were green fields and you could see the city. And now here I am 40 years later and it's houses from here to whatever, and I'm, I go into work on a railway line. And I'm, working in a particular way for a regular employer, which I wasn't.

[00:25:00] Judy Stephenson: So that's, that sort of would've happened over a 30 or 40 year period between 1815 and 1845. And it's quite profound, I think. I think that would've been really notice. For the first time.

[00:25:13] Dror Poleg: All right, and another question from Michael. So you mentioned those kind of early suburbs to the west of the city.

[00:25:18] Dror Poleg: Today, obviously very central, very expensive, but back then a suburbs, were they driven by railroad lines or something else?

[00:25:26] Judy Stephenson: So only the third wave development of late 19th century development is dependent on the railway lines after 1850 or so. Before that the burbs are really about who's got land and who can sell it to the best developer.

[00:25:41] Judy Stephenson: There's a wonderful new biography of Nicholas Barwin by Tim Walker in the London Topographical Society, which basically says how the planning model of buy the land, here's the lease hold for development, here's the lease hold for. The long, the long rental scheme and how they financed all these things.

[00:25:58] Judy Stephenson: But one of the first sub suburbs is just north here of the Bedford Estate. It's called, summers Town, which was, bits of another memorial estate which were sold off to keep that particular dutchy going. And where you've got large scale basically construction. Who want to profit by, who have a modular way of building houses and who can get so many houses up in a season and get a cash flow in.

[00:26:22] Judy Stephenson: So they are driven by the construction industry's supply chains more than any. And some transportation issues.

[00:26:30] Dror Poleg: Yeah, I think in England also here in, in the us but I think in England, I the first real suburbanites were like the, the royals or upper classes that could just basically live in a palace and own land and didn't have to work in the city or have anything to do with it.

[00:26:43] Dror Poleg: And then, Those that had a coach or could the upper class merchants maybe could move out of the city cuz they wanted to live , like a aristocrats.

[00:26:51] Judy Stephenson: Thi this is, and the city particularly the 18th century city is planned around the, there's the garden square is the predominant way that the rich like to live.

[00:26:58] Judy Stephenson: Because they think it's airy and love. There's a pile of poo, literally poo in the corner. Do you what I mean? Because, the way of dealing with rubbish is not what we would consider, healthy. But these idea that these garden squares, give you fresh air, you're away from the animals.

[00:27:11] Judy Stephenson: However, at the hint of plague or cholera or anything, They take off out of the city as soon as they can. And of course, the poorer left behind, unable to afford,

[00:27:20] Dror Poleg: The trans and the garden square for Americans is like those cute little parks that you see in neighborhoods in London in Notting Hill or Marylebone or Mayfair, where you have a bit like in Gramercy in New York, which is a rare a rare style, but a very British, but in, in London, there's much more of that.

[00:27:33] Dror Poleg: Absolutely.

[00:27:34] Judy Stephenson: It's Notting Hill. It's Cadogan Square. It, it's got that nice pot in the middle where you think everyone's sitting out having tea in the. Yeah.

[00:27:41] Dror Poleg: All right, so last question for me. So looking ahead, where do you see city's offices homes in 50 years? What can we learn from history as we go through our own?

[00:27:52] Dror Poleg: Great reshuffle triggered by plague, soon looks like financial crisis of some sort, and who knows what other. So I,

[00:28:00] Judy Stephenson: I think that's as dependent on the firm as it is dependent on public investment in city spaces. Firms at the moment are making decisions about they want everybody in the office or they, they want everybody also to be able to work from home, if there's a crisis or, if the offices can't be used for whatever reason. But that fundamentally changes the nature of employment because we're all paid for our. . And if you're not in the office and somebody can see what you're doing, you're not gonna be paid for your time.

[00:28:27] Judy Stephenson: You're gonna be paid for your output, your project fee, as it were. And then there's a question about do you manage people who are working on projects or do you, they employees or are they subcontractors? . So the management decisions that shareholder driven organizations.

[00:28:43] Judy Stephenson: Make about that question about how they make labor productive will affect how we use the office

[00:28:49] Dror Poleg: And if you had to bet on what they will decide and what the outcome will be. Physically, when we look at the city,

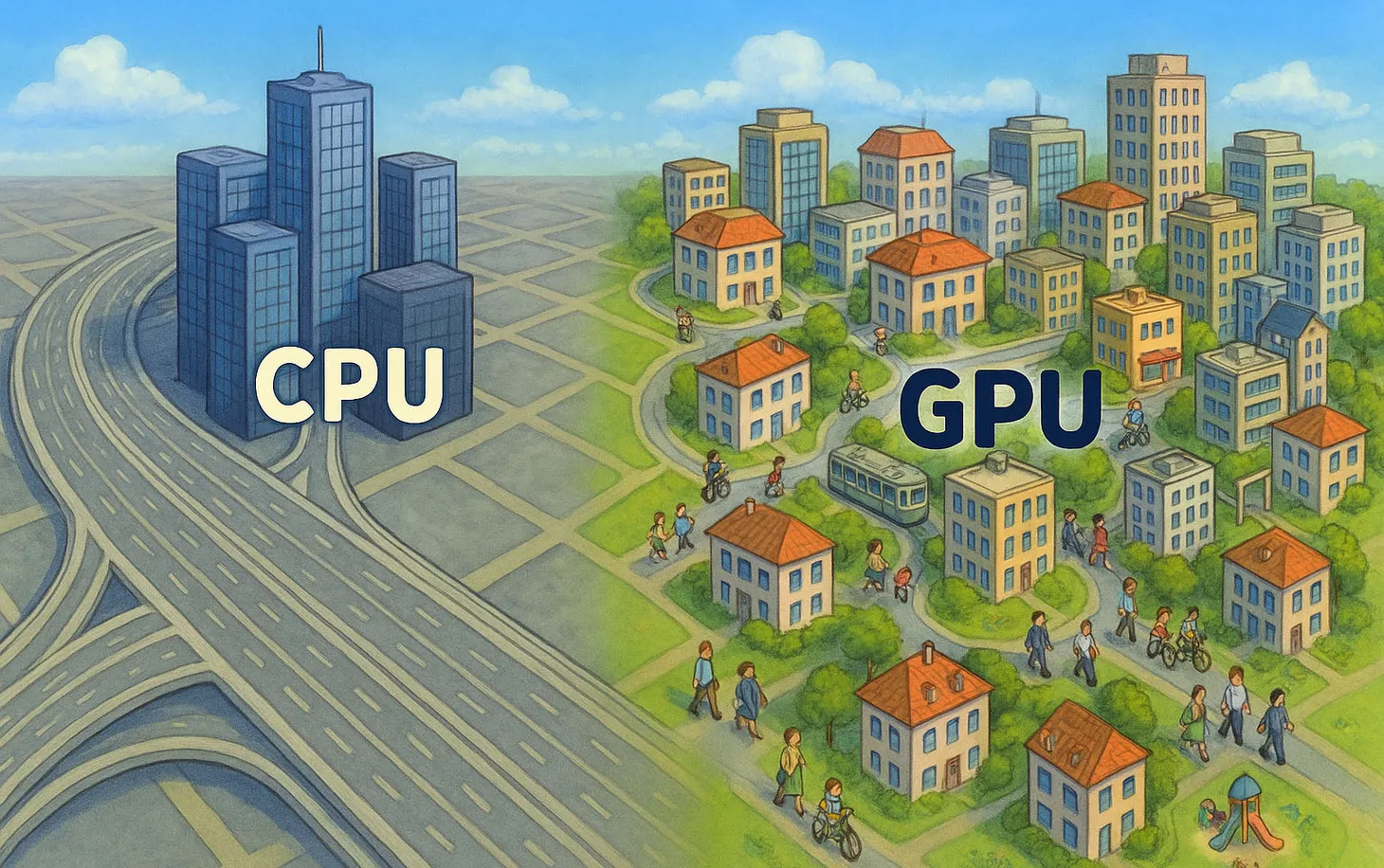

[00:28:55] Judy Stephenson: I think it would be unusual if things became more centralized than they were, because work has never been so centralized as it was at the end of the 20th century.

[00:29:06] Judy Stephenson: , I can't see corporations getting, the trend is actually for corporations not to get bigger in terms of head. You mean? They may be getting cash richer, but very richer, but they're not getting bigger in terms of headcount. So that leaves me to believe that we'll get more desegregated and more there'll be more ver vertical disintegration.

[00:29:23] Judy Stephenson: And what that means is that you're not gonna have any more rock centers. You're not gonna have any more 1251 s you're not gonna have buildings that are assigned to organizations particularly, that are known as places of work for that organization. , you're gonna.

[00:29:37] Judy Stephenson: Buildings that are shared and rented by lots of different players. And it also means that what we think about as suburbia will, actually probably become a nicer place to be because people will be, workers will be there more. And the services around it in terms of , the stuff that was in the nice office kitchen.

[00:29:56] Judy Stephenson: So more mixed

[00:29:57] Dror Poleg: uses basically

[00:29:57] Judy Stephenson: in there. More mixed use. Exactly. And that's culturally interesting as well. So that would be my prediction, is like we couldn't get any more centralized than we were, so it was probably going the other way.

[00:30:06] Dror Poleg: Yeah I tend to agree. I think we, we tend to use the 1950s as a benchmark of normal life, while historically it's such a unique and, yeah, extreme period in so many ways.

[00:30:16] Dror Poleg: Completely. And again not that it's good or bad, but just like thinking that we'll ever go back there, I think it's it's something that we're gr we're slowly learning to, to let go of. So Julie, before I thank you officially and say, . There's another question that I think we don't have to answer today, but it it connects me to an event I have next week.

[00:30:32] Dror Poleg: So Ronen asked about the 15 minute City. Seems to be a very polarizing issue at the moment. People hate it. People love it. Next week I'm hosting another live chat with a Lamberto who is like a, an urban planner and like a very distinguished, interesting thinker about the evolution of cities and transportation networks.

[00:30:50] Dror Poleg: And I think he has a lot to say about that. Less from the conspiracy theory side of things and more just about in thinking, the role of planners in trying to shape economic activities and. And physical environment. So Ronen and everyone else, make sure to join me there as well. And Judy, this was so much fun.

[00:31:06] Dror Poleg: We definitely should do it more frequently than every 12 years. Thank you so much for joining and for sharing your knowledge and insights with us. And I hope to see you soon in sunny. Yes,

[00:31:17] Judy Stephenson: definitely. Thank you Jordan. And sorry,

[00:31:19] Dror Poleg: and I'll have to mention where should people find you? I know that on Twitter, you're @JudyZara, anywhere else in particular where people should

[00:31:26] Judy Stephenson: That's where I, that's where I hang out. Yeah I'm trying write, I'm trying to write the book "Wages Before Machines" at the moment. So I'm not hanging out that much, but that's where I hang out. Yeah.

[00:31:36] Dror Poleg: So yeah, Judy is very prompt at answering to her DMs, regardless of what she just said.

[00:31:41] Dror Poleg: So look her up on Twitter, @Judyzara, follow me as well if you aren't already @DrorPoleg. Thank you all for listening and watching, and thank you again, Judy, and we'll see you all again.

Old/New by Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.