Don’t Sleep With Your Boss.

Yes, old work is done better in person. But new work will ultimately produce the greatest value.

Compassion. Compassion is what I felt watching a recent video of executives trying to bring their employees back to the office. I felt compassion and pity. And then I cringed.

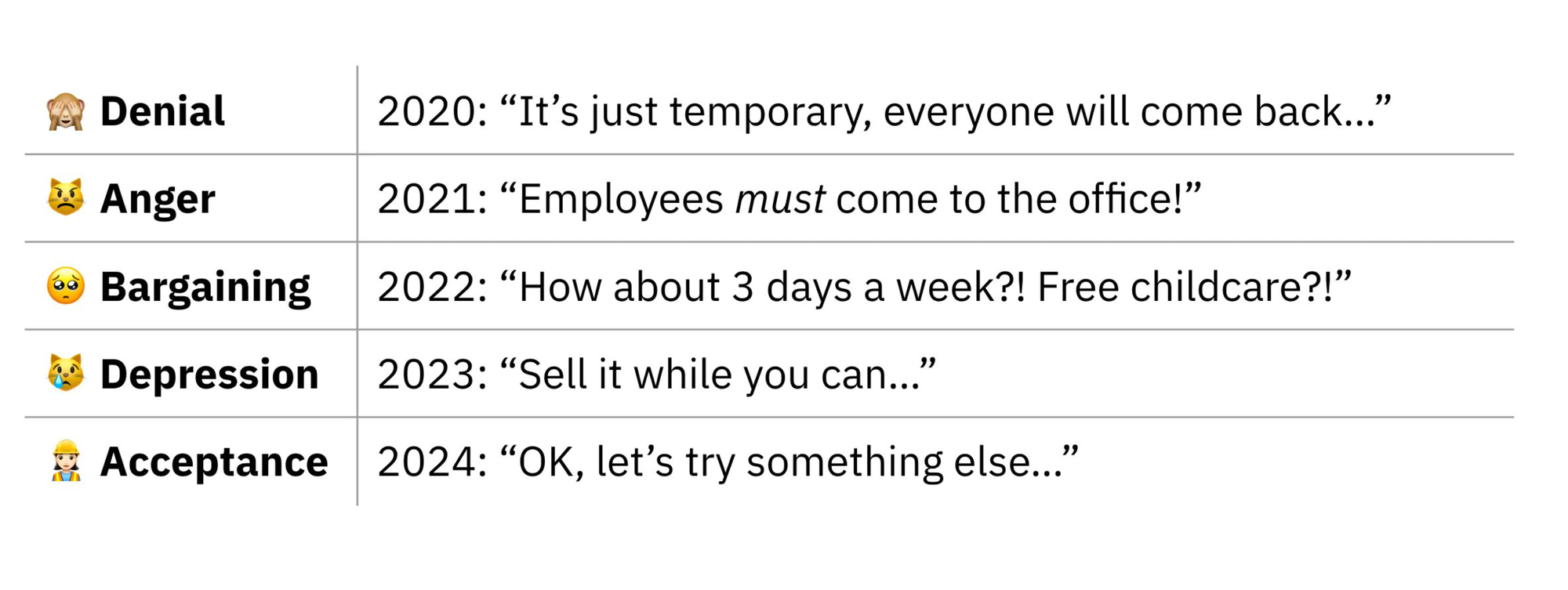

In the video, Internet Brands CEO Bob Brisco tells employees he's no longer "asking or negotiating at this point"; instead, he is "informing" them of how things will be from now on. Like many executives, Brisco is going through the Five Stages of Office Grief: He is done with bargaining, but he doesn't realize that the next step is not victory — it's depression.

The whole video is hilarious and worth a watch. It features executives with virtual backgrounds, awkwardly reading pre-approved text about "organic breakthrough moments" and "crushing the competition." The monologs are interspersed with stock footage of people working in their underwear at home, juxtaposed with someone crushing a soda can at the office cafeteria. The video culminates in a dance sequence. Just like the dog-sacrificng CEO video from last year, it is a classic of the genre.

The parent company of WebMD made an unbelievably bad video telling workers to come back to the office.

— More Perfect Union (@MorePerfectUS) January 11, 2024

Bob Brisco, CEO of Internet Brands, says, "We aren't asking or negotiating at this point."

And somehow that's not even the worst part. pic.twitter.com/YIgmufgISK

I don't think everyone should work from home. And I do believe in-person work has its benefits. But these benefits are now part of an equation that pits them against the benefits of hiring from anywhere, giving people more control over their time, and shifting the focus from presenteeism to actual results. Embracing these other benefits is not just a way of being nice to employees; it is a corporate necessity in a world that is increasingly unpredictable and dependent on specialized talent and optimal matches.

The cost of an office-centric culture is invisible, especially in the short term:

CEOs of office-centric companies can easily delude themselves that their approach to talent does not come at a high cost. There will always be someone that kind of fits the job description and is willing to take the money. But that someone is far less likely to be an outlier that can make an outsize impact on the company’s business.

The whole production function of the economy is changing. But until that process is complete, it is easy to use old benchmarks to convince yourself that limiting your talent pool and micro-managing your employees is the right thing to do. A few recent reports offer examples of this dynamic:

- The Wall Street Journal featured a study that showed "remote workers were promoted 31% less frequently than people who worked in an office" over the past year.

- A separate survey found that "Nearly 90% of chief executives who were surveyed said that when it comes to favorable assignments, raises or promotions, they are more likely to reward employees who make an effort to come to the office."

- And yet another study found that "engineers at a Fortune 500 company who worked in the same building as their teammates received 22% more feedback on their code."

What do these studies actually tell us?

That bosses who like to work at an office favor employees who are willing to come to the office.

I ran a separate survey of movie producers and directors and found they were likelier to promote and compensate actresses who were willing to sleep with them.

I'm joking, I'm joking. I didn't run that survey. But you get the idea: The fact that bosses like and reward certain behaviors does not mean these behaviors are good for business.

And while we're talking about movies, there's an even broader analogy. In the past, movie studios were true gatekeepers: they controlled production and distribution and could pick winners and crown stars. Today, anyone can upload a video and the winners are picked by complex dynamics that involve algorithms and online crowds.

In media, it is already clear how the basic production function has changed. Media production used to be a linear process involving few producers, scarce distribution channels (cinemas, expensive film rolls), and an audience with very little choice. And now it's a chaotic process involving millions of people, multiple cheap distribution channels, and an audience flooded with other things to watch. In such a world, the biggest winners are those who can facilitate rapid experimentation, tap into the broadest talent pool, and double down on whatever seems to appeal to the audience. TikTok does this well.

The same production function is trickling down to the rest of the economy. On the marketing front, all consumer products depend on content and social media and are subject to the same dynamics. This is true for cosmetics as it is for cars and real estate. But even on the production front, value is concentrated in the few companies that are able to tap into the largest possible talent pool and are agile enough to take advantage of emerging opportunities.

So, if you want to understand where the world is going, don't ask average bosses what they prefer or who they favor. Instead, ask exceptional bosses how they work. One of these bosses is Jensen Huang, the CEO of Nvidia — the fastest-growing company of the past few years. Nvidia designs and configures some of the most advanced hardware ever made, and it does so by tapping into thousands of employees in hundreds of locations who have incredible freedom in determining how and when they work.

This does not mean your company should adopt exactly the same approach. It might actually make sense for your business to have everyone in the same place, or to work strict schedules, or, for that matter, to wear a uniform. But whatever your policy, it should be tied to a clear purpose and considered against the benefits of alternative approaches. The fact that your managers don't know how to manage a distributed workforce or motivate top talent is not a reason to force all your employees into a rigid office schedule; it's a reason to find new managers.

Have a great week. I'm sending fewer newsletters these days since I am head-down working on my next book. More on that soon!

I research technology's impact on how humans live, work, and invest.

💡Book a keynote presentation for your next offsite, event, or board meeting.

❤️ Share this email with a friend or colleague

Old/New by Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.