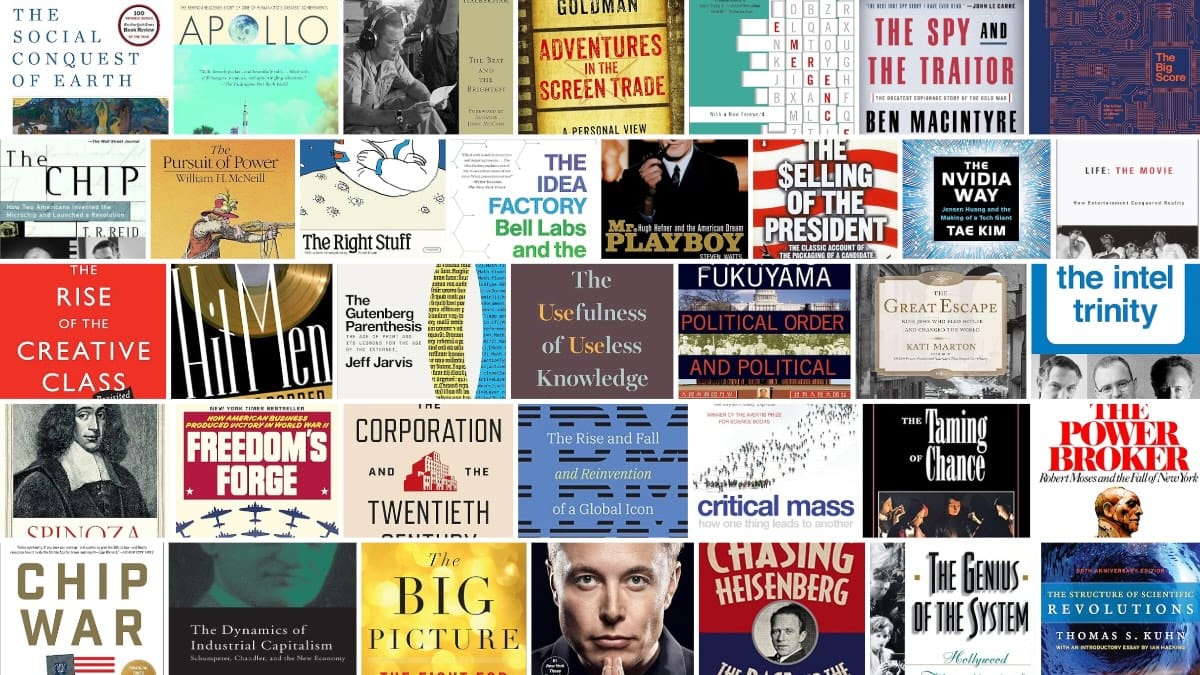

Books I enjoyed this year.

Below are books I read and enjoyed this year, not necessarily for the first time. The list includes books I took notes on, meaning I found them worthwhile. I included affiliate links to Amazon in case you'd like to explore further. As an affiliate, I earn a small commission on any book sold.

The Idea Factory, a history of Bell Labs, where some of the most important inventions of the 20th Century — particularly, the transistor — emerged. Bell was also a pioneer of recruiting brilliant people and letting them work on whatever they wanted as long as it was tangential to “communication.”

The point of this kind of experimentation was to provide a free environment for “the operation of genius.” His point was that genius would undoubtedly improve the company’s operations just as ordinary engineering could. But genius was not predictable. You had to give it room to assert itself.

Chip War, a history of semiconductors from a geopolitical angle. Also, a great exploration of how the global economy operates and why it’s often hard to tell where economic power ends and where military power begins.

Three days after Noyce and Moore founded Fairchild Semiconductor, at 8:55 p.m., the answer to the question of who would pay for integrated circuits hurtled over their heads through California’s nighttime sky. Sputnik, the world’s first satellite, launched by the Soviet Union, orbited the earth from west to east at a speed of eighteen thousand miles per hour.

The Social Conquest of the Earth, a classic by E.O. Wilson about how social animals — from ants to humans — operate and thrive.

We have created a Star Wars civilization, with Stone Age emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.

The Power Broker, the epic story of how Robert Moses reshaped America by filling various public roles in New York City and State.

To build his highways, Moses threw out of their homes 250,000 persons—more people than lived in Albany or Chattanooga, or in Spokane, Tacoma, Duluth, Akron, Baton Rouge, Mobile, Nashville or Sacramento.

The Chip, a somewhat detailed history of the invention of the microprocessor. Worth reading if you're really into the topic and/or looking for a specific detail.

If you want to know why modern man has settled on a base-10 number system, just spread your hands and count the digits. All creatures develop a number system based on their basic counting equipment; for us, that means our ten fingers. The Mayans, who went around barefoot, used a base-20 (vigesimal) number system; their calendars employ twenty different digits. The ancient Babylonians, who counted on their two arms as well as their ten fingers, devised a base-12 number system that still lives today in the methods we use to tell time and buy eggs.

Mr. Playboy, a biography of Hugh Hefner, which was much more important and interesting than most people assume. Ultimately, it is a book about America.

n the 1950s, the magazine reflected hip, urban dissatisfaction with the stodgy conformism of the Eisenhower era as it critiqued middle-class suburbanism, the Beat Generation, and the Cold War crusade against communism. In the 1960s, Hefner helped fan the flames of the civil rights movement, the antiwar crusade, the countercultural revolt, and the emerging feminist struggle. In the 1970s, Playboy personified both the “Me Generation” and the economic contractions of the era, while the 1980s saw it become a foil for, and target of, the Reagan Revolution.

The Nvidia Way, the story of the world’s hottest company in 2024 and its unique approach to management, compensation, and talent.

the company had a policy of hiring quickly—but also of firing fast if a new employee wasn’t working out. Jensen’s primary guidance to all of his hiring managers was simple: “Hire someone smarter than yourself.”

The Rise of the Creative Class, the classic book about how work and cities are changing. Twenty years on, I still return to it.

During the 1980s and 1990s, many cities in the United States and around the world tried to turn themselves into the next “Silicon Somewhere” by building high-tech office parks or starting up venture capital funds. The game plan was to nourish high-tech start-up companies or, in its cruder variants, to lure them from other cities. But it quickly became clear that this wasn’t working.

The Big Picutre, a chronicle of how technology and big brands changed hollywood in the recent past, particuarly with the rise of Marvel and other franiches and the parlalel rise of Netflix.

The hundreds of millions of dollars in profits created by one Avengers or Jurassic or Spider-Man film dwarf the profits of Captain Phillips, The Social Network, and American Hustle combined. And then there are the sequels, consumer products, and other sources of revenue that come along with a hit franchise film.

The Intel Trinity, a history of one of the most important companies of the 20th Century and the semiconductor industry it reshaped. It revolves around the company's founders and legendary CEOs — Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, and Andy Grove.

Through the 1950s, they built upon the policies that the companies had first implemented during the war. Soon HP was famous for flexible hours, Friday beer busts, continuing-education programs with Stanford, twice daily coffee and doughnut breaks—and most important, employee profit sharing and stock options.

The Big Score, an early (1985) history of Silicon Valley, providing contemporary perspective on some of the most exciting companies and people in tech.

At the time of Stanford University’s opening, in 1891, the New York Mail and Express wrote with characteristic subtlety that “the need for another university in California is about as great as that of an asylum for decayed sea captains in Switzerland.”

The Selling of the President, about how Richard Nixon became president through meticulous usage of a new medium.

"We re going to carry New York State, for instance, despite the Times and the Post. The age of the columnist is over. Television reaches so many more people."

The Taming of Chance, a great book about the history of probability and human thinking about risk and uncertainty.

The first American census asked four questions of each household. The tenth decennial census posed 13,010 questions on various schedules addressed to people, firms, farms, hospitals, churches and so forth. This 3,000-fold increase is striking, but vastly understates the rate of growth of printed numbers: 300,000 would be a better estimate.

Freedom’s Forge, the incredible story of how American industry won World War II.

When Roosevelt announced his plans for 50,000 planes a year, Hitler branded the number a fantasy. He scoffed, “What is America but beauty queens, millionaires, stupid records, and Hollywood?”

Elon Musk, a Walter Isaacson biography of a Twitter troll. My particular interest was in the motivations and machinations behind the founding of OpenAI.

In February 2023, he invited—perhaps a better word is “summoned”—Sam Altman to meet with him at Twitter and asked him to bring the founding documents for OpenAI. Musk challenged him to justify how he could legally transform a nonprofit funded by donations into a for-profit that could make millions. Altman tried to show that it was all legitimate, and he insisted that he personally was not a shareholder or cashing in. He also offered Musk shares in the new company, which Musk declined.

IBM, a history of the first tech giant. In particular, I was interested in the motivations behind the (belated) development of the personal computer and the decision not to own the operating system or software in general.

The cost of microcomputers kept falling faster than anyone predicted while simultaneously they were becoming more powerful—Moore’s Law, which held that the processing speed of chips doubled and chip prices halved roughly every 18 months, was at work. Compaq and others introduced ever lighter and more powerful machines without anything like IBM’s review process. In the early 1980s, IBMers consistently underestimated the size of the PC market, how fast it would grow, and how its base technologies were evolving.

The Spy and the Traitor, the gripping story of one of the great spies of the cold war. Such a fun read.

For many years, the KGB used the acronym MICE to identify the four mainsprings of spying: Money, Ideology, Coercion, and Ego.

The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge, about why aimless exploraiton often leads to humanity’s greatest technological breakthroughs. Written by the founder of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton and helped relocate Albert Einstein and other European geniuses to America.

As von Neumann observed in 1946, “I am thinking about something much more important than bombs. I am thinking about computers.”

Spinoza, a short Ian Buruma biography of one of my favorite people. Unlike most other biographers, Buruma acknowledges that people always project their own worldviews on Spinoza and interpret him to be “on their side” — whether they are atheists, pantheists, Jews, gentiles, Protestants, libertarians, or socialists. All Spinoza biographies are flawed, and so is this one, but it provides a valuable perspective.

In his list of ways to perceive truth, the intuitive understanding of nature was rated more highly than the rationalist, scientific search for truth, and both were of course vastly superior to reliance on gossip, received opinions, and other external influences.

Life: The Movie, about how entertainment reshaped politics, business, and life itself by the great Neal Gabler.

As Boorstin observed, the deliberate application of the techniques of theater to politics, religion, education, literature, commerce, warfare, crime, everything, has converted them into branches of show business, where the overriding objective is getting and satisfying an audience.

Adventures in the Screen Trade, the memoirs and observations of legendary screenwriter William Goldman (The Princess Bride).

the single most important fact, perhaps, of the entire movie industry: NOBODY KNOWS ANYTHING.

Political Order and Political Decay, Francis Fukuyama’s 2014 thinking about institutions and history. Always interesting and well-written.

Human beings by nature are also norm-creating and norm-following creatures. They create rules for themselves that regulate social interactions and make possible the collective action of groups. Although these rules can be rationally designed or negotiated, norm-following behavior is usually grounded not in reason but in emotions like pride, guilt, anger, and shame.

Apollo, about America’s decisive race to the moon.

About 140 engineers (including the Canadian contingent), most of them youngsters, with borrowed quarters and a strained budget, were supposed to put a man into space and redeem America’s technological prestige in the eyes of the world.

The Right Stuff, a more colorful account of the people who went to the moon.

In time, the Navy would compile statistics showing that for a career Navy pilot, i.e., one who intended to keep flying for twenty years as Conrad did, there was a 23 percent probability that he would die in an aircraft accident. This did not even include combat deaths, since the military did not classify death in combat as accidental.

Critical Mass, 20-year-old book about the history of ideas, particularly ideas about “cascades” and “phase transitions” that migrated between Physics and the Social Sciences. Philip Ball is kind of a Malcolm Gladwell for grownups.

Regardless of what we believe about the motivations for individual behavior, once we become part of a group we cannot be sure what to expect.

The Great Escape, about the brilliant Hungarian Jews who left Europe for America and reshaped physics, art, and culture.

By 1910, Jews made up half the lawyers and doctors, one-third of the engineers, and one-quarter of artists and writers in Budapest. Jews were largely responsible for Budapest’s transformation into a bustling financial and cultural hub. Over 40 percent of the journalists working at the city’s thirty-nine daily newspapers were Jews.

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions is a not-so-easy-to-read classic that is still controversial and relevant 60 years after it was initially published.

Max Planck, surveying his own career in his Scientific Autobiography, sadly remarked that “a new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

Hit Men, a 1990s book about how the pop music industry works or used to work.

The pop-music business had a golden principle: There was an enormous amount of money to be made with a hit record, and no money to be made without one. You might have a hundred artists on your pop roster, but most of them were going to lose money. A handful of stars, the Billy Joels, the Michael Jacksons, the Barbra Streisands, compensated for all the losers.

The Genius of the System, about how Hollywood used to work in the middle of the 20th Century.

The Hollywood studio system emerged during the teens and took its distinctive shape in the 1920s. It reached maturity during the 1930s, peaked in the war years, but then went into a steady decline after the war, done in by various factors, from government antitrust suits and federal tax laws to new entertainment forms and massive changes in American life-styles. As the public shifted its viewing habits during the 1950s from “going to the movies” to “watching TV,” the studios siphoned off their theater holdings, fired their contract talent, and began leasing their facilities to independent filmmakers and TV production companies. By the 1960s MGM and Warners and the others were no longer studios, really. They were primarily financing and distribution companies for pictures that were “packaged” by agents or independent producers—or worse yet, by the stars and directors who once had been at the studios’ beck and call.

Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism and The Corporation and the Twentieth Century, two excellent and original books by Richard Langlois, about how Economists and managers thought they “solved” the economy and got everything under control — about the unique conditions that sustained this illusion and how it all collapsed. "The Corporation" is more accessible to general readers.

The central fact about American manufacturing industry in the years after World War II was its dominance in a world still digging out from a cataclysmic war. In the late 1940s, the US was responsible for more than 60 percent of manufactures in the world.

Emergence by Steven Johnson is an older book about complexity that is still worth a read.

What features do all these systems share? In the simplest terms, they solve problems by drawing on masses of relatively stupid elements, rather than a single, intelligent “executive branch.”

The Pursuit of Power, a history of military technology, from the year 1000 to the year 2000.

Alterations in armaments resemble genetic mutations of microorganisms in the sense that they may, from time to time, open new geographic zones for exploitation, or break down older limits upon the exercise of force within the host society itself.

Chasing Heisenberg is a biography and an attempt to decipher the motivations of one of the greatest physicists.

In February 1939, a Bund rally at Madison Square Garden in New York City drew 20,000 supporters. Marching to the beat of snare drums, men in Nazi uniforms carrying American flags and swastikas had paraded into the Garden where they were greeted by rally organizers.

The Best and the Brightest, David Halberstam’s classic account of JFK’s cabinet of bright people who drove America into a ditch in Vietnam.

...they made one fatal mistake; they forgot that in the Cuban missile crisis it was the Russians, not the Cubans, who had backed down. The threat of American power had had an impact on the Soviets, who were a comparable society with comparable targets, and little effect on a new agrarian society still involved in its own revolution. Thus, though they were following the same pattern as they had in the missile crisis, they lacked a sense of history, and what had seemed so judicious before became injudicious in Vietnam. The bluff of power would not work and we would be impaled in a futile bombing of a small, underdeveloped country, an idea which repelled most of the world and increasing numbers of Americans.

The Gutenberg Parenthesis, about the history of print, and, more broadly, about how technology shapes culture and cognition.

“Permit me to express the opinion that telegraphing is not such a business as women should seek to engage in,” wrote J.W. Stover in a letter to The New York Times in 1865, opposing membership in the National Telegraphic Union to women. “It brings them in contact with too many rough corners of the world, and requires an understanding of such matters as a womanly woman cannot be expected to possess.”

That's it from me. Have you read any of these? What did you think? Anything else along the same lines that I should read?

Happy New Year!

Best,

🎤 Are you looking for a keynote speaker for your next event, corporate offsite, or investor meeting? Every year, I inform and inspire thousands of executives across the world. Visit my speaker profile to learn more and get in touch with my agent.

Old/New by Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.