The Talent Portfolio

Individual people are the next big asset class.

This is the second part of Betting the Firm. In Part I, we explored why the company of the future will look like a venture fund. In Part II, we look at how finance will evolve to invest directly in talented individuals, rather than companies. Instead of investing in a portfolio of companies, we will invest in a portfolio of people.

Firms and Films

A rabbi friend once explained to me his drinking strategy: “I only need one glass to feel good. I just never know which glass it is." This tragic approach to alcohol makes more sense when it comes to talent. Google also needs one (or a handful) of knowledge workers to come up with the next big thing. But it never knows which ones.

Film producers in the 20th Century faced a similar challenge. An individual “star” could make a dramatic impact on a film’s financial performance. This left producers with two options: pay lots of money to hire a known star; or try to discover a potential star before she gets expensive.

But film producers did not just hire stars; they also created them. Film stars did not simply emerge; someone had to pick, promote them, and build their image. As a result, even the most beautiful and talented people had limited power. At best, they had to suck up to producers and directors. At worse, they had to do much more. As Marylin Monroe described her early days in Hollywood: “I spent a great deal of time on my knees."

Producers and directors were powerful because of scarcity. Films were expensive to produce and distribute and only a relatively small number made it to an actual cinema each year. Talent and looks were important, but having a production and marketing budget and relationships with distributors and media outlets usually mattered much more.

Software in the 21st Century is not governed by the laws of scarcity; instead, it is governed by the laws of abundance. Software is cheap to produce and almost free to distribute. Software stars can emerge without anyone’s permission. A 19-year-old Mark Zuckerberg in a dorm room can launch a new social network that overpowers the world’s largest media companies.

But Zuckerberg could not have scaled his company on his own. He had to hire other stars. And unlike Holywood executives, he couldn’t simply pick adequate candidates who sucked up to him or provided special favors. He had to hire the best. Early on, he could spend time with potential candidates and maybe — maybe — gauge their potential. But as a company grows, it becomes impossible for the original star-founder to vet every new hire.

What happens then?

That’s where two other differences between films and software kick in.

Throwing Darts

Software is infinitely scalable. The highest-grossing film of all time, Avatar, brought in just under $3 billion since it premiered in 2009. Facebook only needs two weeks to generate the same amount of revenue. Google does it in six days.

And because software is relatively cheap to produce, at least initially, companies can employ multiple people on multiple projects and see which ones pan out. Holywood studios are also heavily reliant on a handful of blockbusters to cover the cost of numerous other productions. But historically, the high cost of making and distributing a movie meant producers could only throw a handful of darts at the board. And even when they hit the bullseye, they could not generate Google or Facebook-level profits.

This risk-reward ratio meant that even successful producers could go bankrupt if they made one bad film. In contrast, Google can launch multiple flops and stay alive. One Gmail or AdSense can pay for plenty of failed Orkuts, Froogles, and Google Pluses, as well as hundreds of other experiments that failed even to launch.

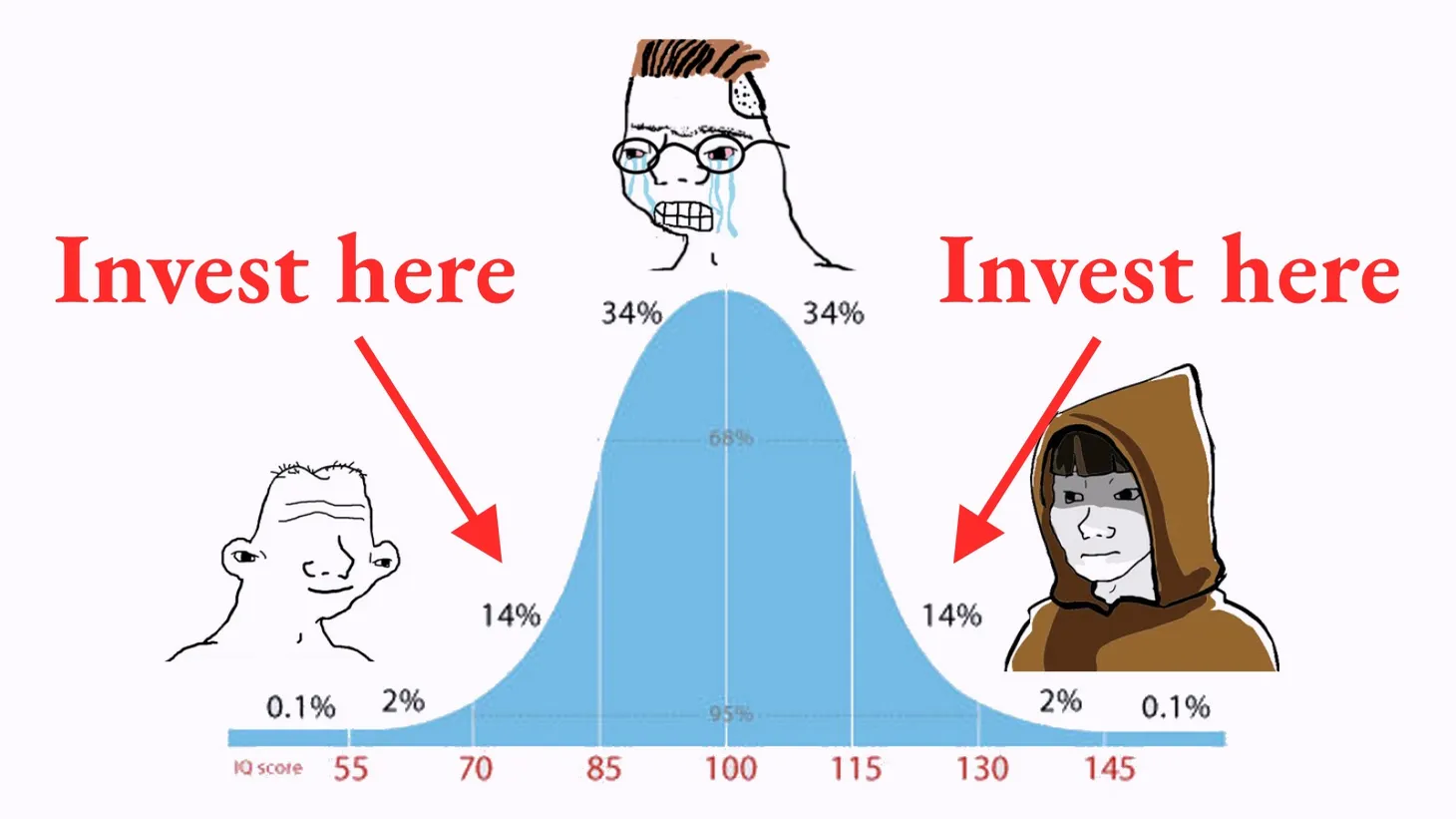

Software companies cannot know in advance which person will come up with an outlier idea or make an outlier contribution. But they can afford to bet on thousands of potential star individuals. And that’s exactly what they’re doing.

Google employs tens of thousands of engineers, paying them anywhere from $200,000 to $1,000,000 a year. The steady-state contribution of most of these individual engineers is not worth that salary. But in aggregate, it is worth paying all of them for the chance that a handful will come up with an amazing breakthrough in any given week/month/year. Such a breakthrough could be the next Gmail, but it could also be a less-glamorous solution that increases revenue or cuts the cost of existing services.

Google is not just betting on multiple projects. It’s also betting on multiple people. And the economics of software development make such large-scale betting worthwhile.

But not every company can afford to pay billions of dollars to tens of thousands of people in the hope that a few of them will come up with a multibillion-dollar idea. This arrangement is not optimal for the employees, not optimal for society, and not even optimal for the tech giants themselves.

Is there an alternative? Before we get to that, let’s consider what’s wrong with the current arrangement.

High Floor, Low Ceiling

In 2004, William Nordhaus published a seminal economic paper that looked at how the profits from innovation are distributed. Analyzing data from 1955-2000, Nordhaus found that “most of the benefits of technological change are passed on to consumers rather than captured by producers.” The companies that came up with an innovation captured only 2.2% of the actual “social surplus” it generated.

Tech companies and investors often refer to this study to argue that their benefit to society outweighs any concerns about the amount of profits they make or the amount of power they wield. This argument has merit, but it obscures an important question about the distribution of rewards from innovation within tech companies.

There’s an inherent misalocation of rewards in the big tech model. If an employee comes up with an amazing solution and it gets adopted by the company, the employee receives a fraction of the value she created. On the other hand, if an employee comes up with an amazing solution and quits in order to build her own company, Google gets nothing despite paying that employee a hefty salary and betting on them when no one else would.

More importantly, there’s a misalignment of incentives at the societal level. Suppose innovation is indeed dependent on a series of bets on individual projects and people. In that case, it makes no sense to let a handful of companies accumulate the majority of the rewards from such bets and to limit the rewards that individuals can reap from coming up with great ideas (and by “ideas,” I mean practical solutions to meaningful problems).

Tech companies don’t only pay some people too little; they also pay most people too much. As my friend Ben often tells me, if tens of thousands of our scientists and engineers get a massive salary regardless of what they end up producing, they have a lower incentive to solve actual, meaningful problems. Big tech sucks in a lot of talent and does not put most of this talent to good use.

This is not an argument for socialism. I have no problem with innovators making lots of money from their work. The problem is that actual innovators are not making enough, while potential innovators are made rich before they fulfill their potential. This happens because giant tech companies currently have a near-monopoly on betting on talent. No one else can afford to “seed” tens of thousands of people and see which ones come up with something amazing.

Society faced a similar problem before.

Investing in Talent

The venture capital industry emerged to enable HP-type bets on new businesses outside giant companies and to enable giant investors to diversify into assets that are not correlated with traditional stocks and bonds.

Innovation has since become more important and more elusive, and investors are more hungry for alternative assets than they have ever been. This calls for a further evolution of the venture capital model.

Instead of investing in companies before they become big, investors need to invest in individuals before they form companies. Talent itself must become an investable asset. And it is.

As I pointed out in The Ponzi Career and NFTs and the Future of Work, technology lowers the cost of investing directly in the future earnings of individual people. Thanks to Decentralized Finance (and cryptocurrencies), such investments are available to anyone, allowing talented people to tinker with ideas without getting a Big Tech job and enabling society as a whole to share the risks and the rewards of innovation. This way, more talented people are able to and are incentivized to work on things that society deems viable.

Did I bring you all this way to talk about crypto? Yes. But I’m not really talking about crypto. I am talking about a different approach to economics. Crypto offers a possible path. But there may be others.

New ways to finance innovation will not necessarily lead us to a better place. “Things that society deems viable” could mean anything from alternative energy to cat memes. And removing the floor below and the ceiling above our best and brightest might lead to growing inequality and social unrest. But whether we like it or not, finance is evolving towards direct investment in "portfolios of people."

I’ll continue to explore the possible consequences of these changes. Subscribe, so you don’t miss it.

Old/New by Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.