Airbnb's Double Disruption

🎧 An audio version of this article is available below, on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and beyond.

What's next for the housing market? Next week, I'm presenting my latest thoughts on the future of housing, followed by a Q&A moderated by AppFolio's Sean Forster. Click here to register. It's free.

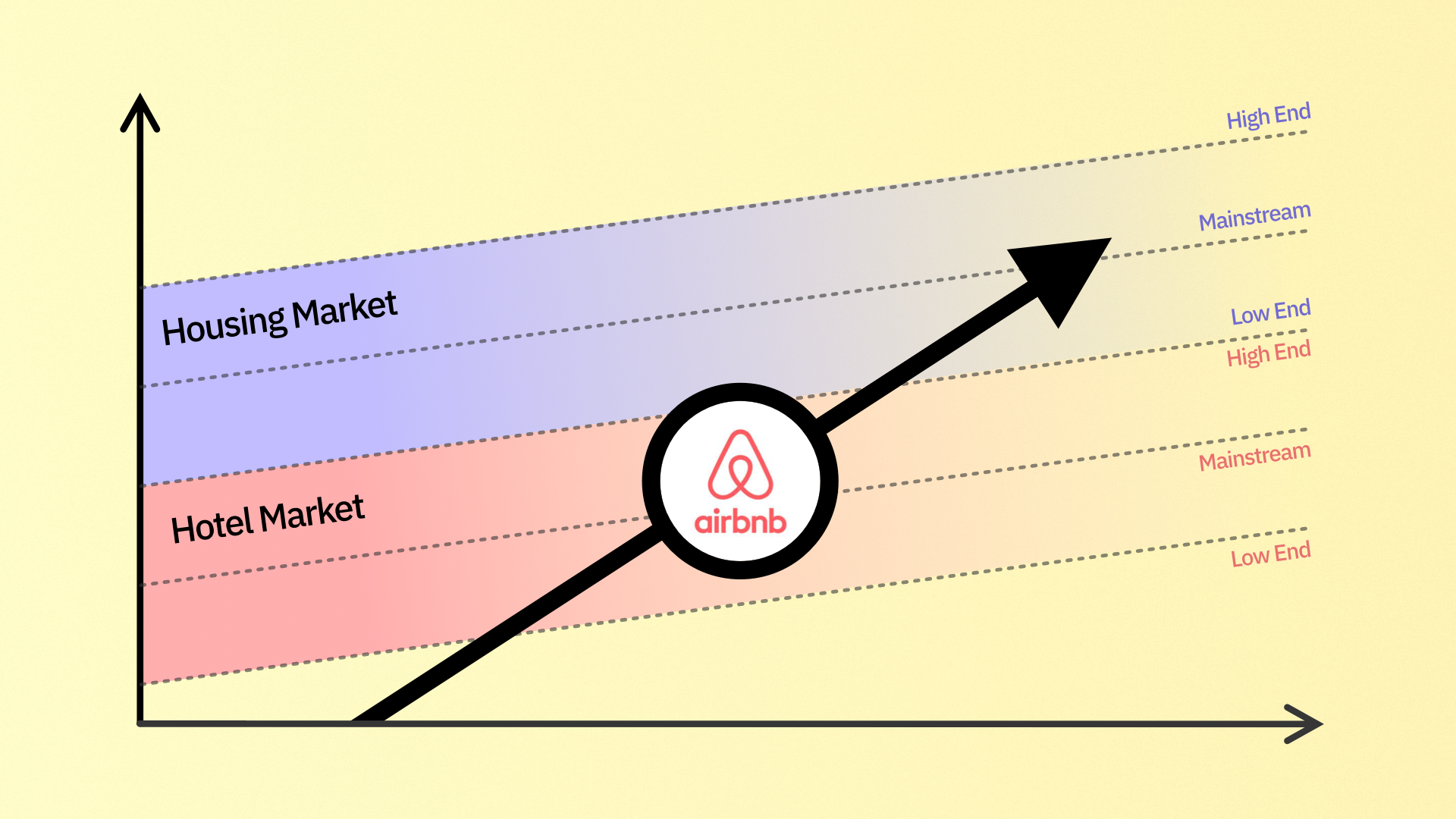

This morning's news gave me some new material to work with. In my classes and keynotes, I often ask my audience: What market is Airbnb disrupting?

The obvious answer is the hotel market, formally known as the "lodging market." In The Innovator's Dilemma, Clay Christensen described how disruptive innovations initially target the low end of a market. Such disruptions cater to people who are price-sensitive or even people who can't afford other products at all.

In the hotel market, Airbnb followed this playbook to a tee. It initially catered to people who could barely afford a hotel — people willing to sleep on an airbed in a stranger's apartment. Gradually, it started catering to customers who could afford a budget hotel but wanted a different location or experience. Over time, it began to cater to mainstream travelers and even to high-end families and groups.

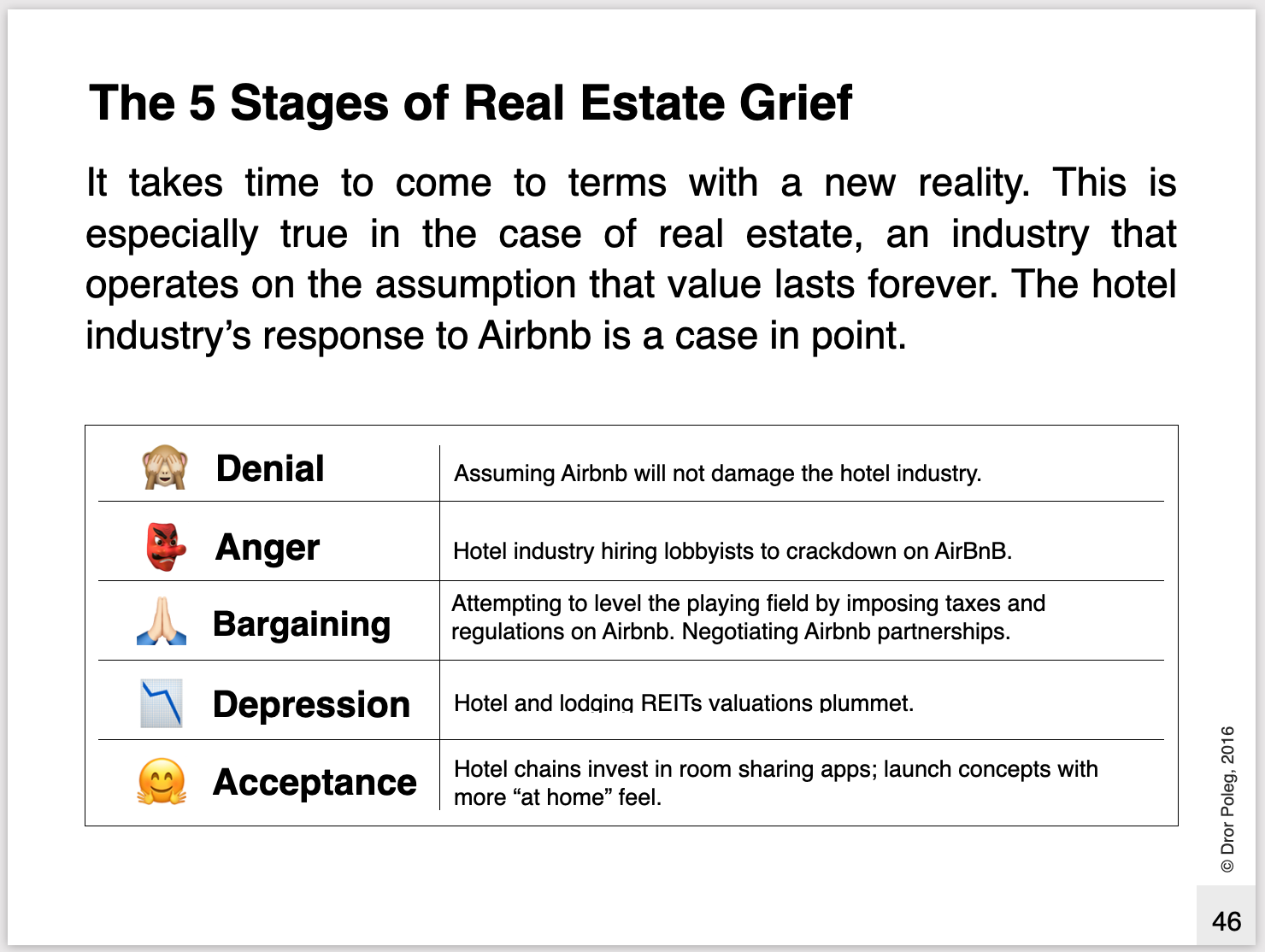

That trajectory was not obvious, and many people expected Airbnb to fail or remain a niche player that doesn't affect the overall market. Back in 2016, I described "The 5 Stages of Real Estate Grief" — the process by which hotel operators and landlords come to terms with a new reality. Airbnb was not going away. It was not about to be outlawed. And it was not destined to remain a small company that "real" hotels could ignore.

Airbnb became the largest hospitality brand in the world. Its market cap is higher than Marriott, Hilton, and Accor — and at some point, it got even higher than all three combined. Traditional hotel companies had to restructure their business in response — they launched their own home-sharing sites and altered some of their properties to cater to families and have a more authentic feel. Some of them even started listing their own hotel rooms on Airbnb.

But Airbnb didn't stop there. In 2019, I pointed out in my book, Rethinking Real Estate, that Airbnb's ultimate destination is not the hotel market but the housing market.

"Airbnb used apartments to disrupt hotels, but its ultimate impact will be much more disruptive to those who manage apartments than to those who manage hotels...

Why should it take 30 seconds to find, pay, and move into an apartment on Airbnb while it takes 30 days to find, pay, and move into the same apartment through the traditional residential leasing process? It doesn’t make sense, and it won’t last."

I had such high conviction in this outcome that I chose to combine the "housing" and "lodging" sections in my book into a single section (office, retail, and industrial all had their own sections).

For a while, Airbnb did not show a real interest in the housing market. Instead, it chose to compete more fiercely with hotels and online travel agents. This made me less optimistic about its prospects.

But then Covid hit, and Airbnb started to make clear steps in the direction I had outlined. In the middle of 2021, CEO Brian Chesky reported that 24% of Airbnb's revenue came from bookings of 28 days or longer. In January 2022, Chesky reported that over the previous year, 100,000 Airbnb guests booked stays for three months or longer.

Airbnb developed an appetite for more extended stays and the overall housing market. But it was unclear whether the company was genuinely focused on the vision I outlined.

This morning, it became clear. As Konrad Putzier reports in the Wall Street Journal:

"Airbnb is launching a listing service for rental apartments with some of the biggest landlords and property managers in the country, a bid to expand its business in multifamily buildings...

The site will act as a listing platform for rental apartments, similar to Zillow or Apartments.com, but it will only include units where short-term sublets are allowed. Tenants who sign a lease can sublease their units for a fixed number of days a year..."

With this move, Airbnb is setting its sites on the rental housing market as a whole. It would help it secure more supply for short-term stays, but it ultimately represents a much larger opportunity than the hotel market. As I pointed out in my book, "hotels" and "apartments" have a shared history and future. In the 19th Century, hotels were synonymous with apartment buildings: families often resided in hotels for months, and apartment buildings offered services such as communal dining rooms, furnished rooms, "turndown," and laundry.

Airbnb's trajectory shows how disruption in one market ultimately affects others. It'll be interesting to see how far they go.

As mentioned, I'm giving a presentation next week about the most interesting trends affecting the housing markets. It is free and open to the public. Click here to register.

Can't make it to the live session? Register, and we'll email you the recording.