Airbnb is WeWork

You can change a giant market even if you don't control it.

You can change a giant market even if you don't control it.

🚨 Tomorrow, I'm speaking at a free webinar about the future of housing. I'll share some key trends and analysis — and answer any questions you may have. Click here to register. It's free.

🎧 The audio version of this article is available below and on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and beyond.

Last week, I wrote about Airbnb's growing appetite for the long-term rental market:

"In the middle of 2021, CEO Brian Chesky reported that 24% of Airbnb's revenue came from bookings of 28 days or longer. In January 2022, Chesky reported that over the previous year, 100,000 Airbnb guests booked stays for three months or longer.

Airbnb developed an appetite for more extended stays and the overall housing market. But it was unclear whether the company was genuinely focused on the vision I outlined. This morning, it became clear."

It became clear last week when Airbnb announced a new rental listings platform — not for short stays, but for regular apartments with standard leases.

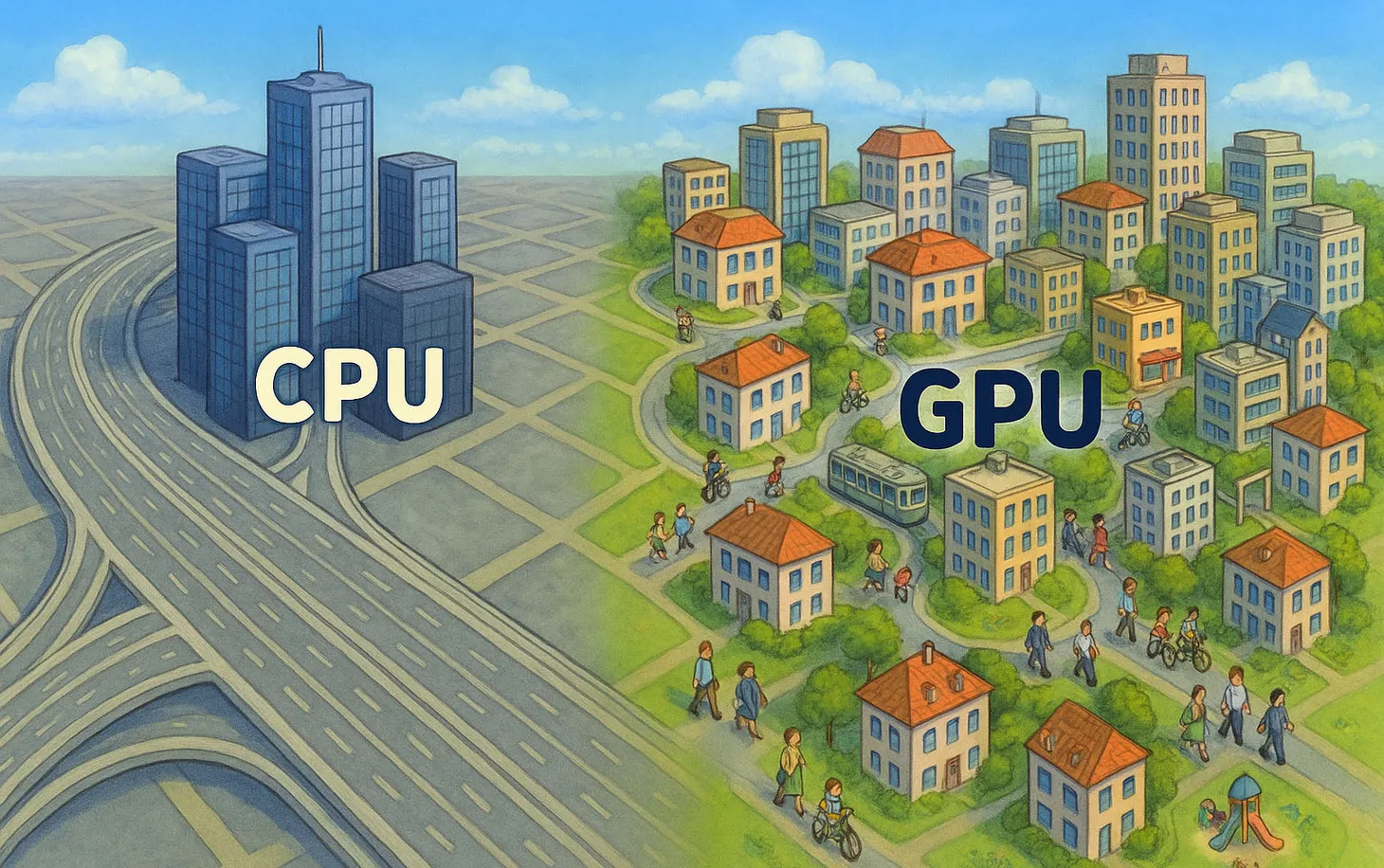

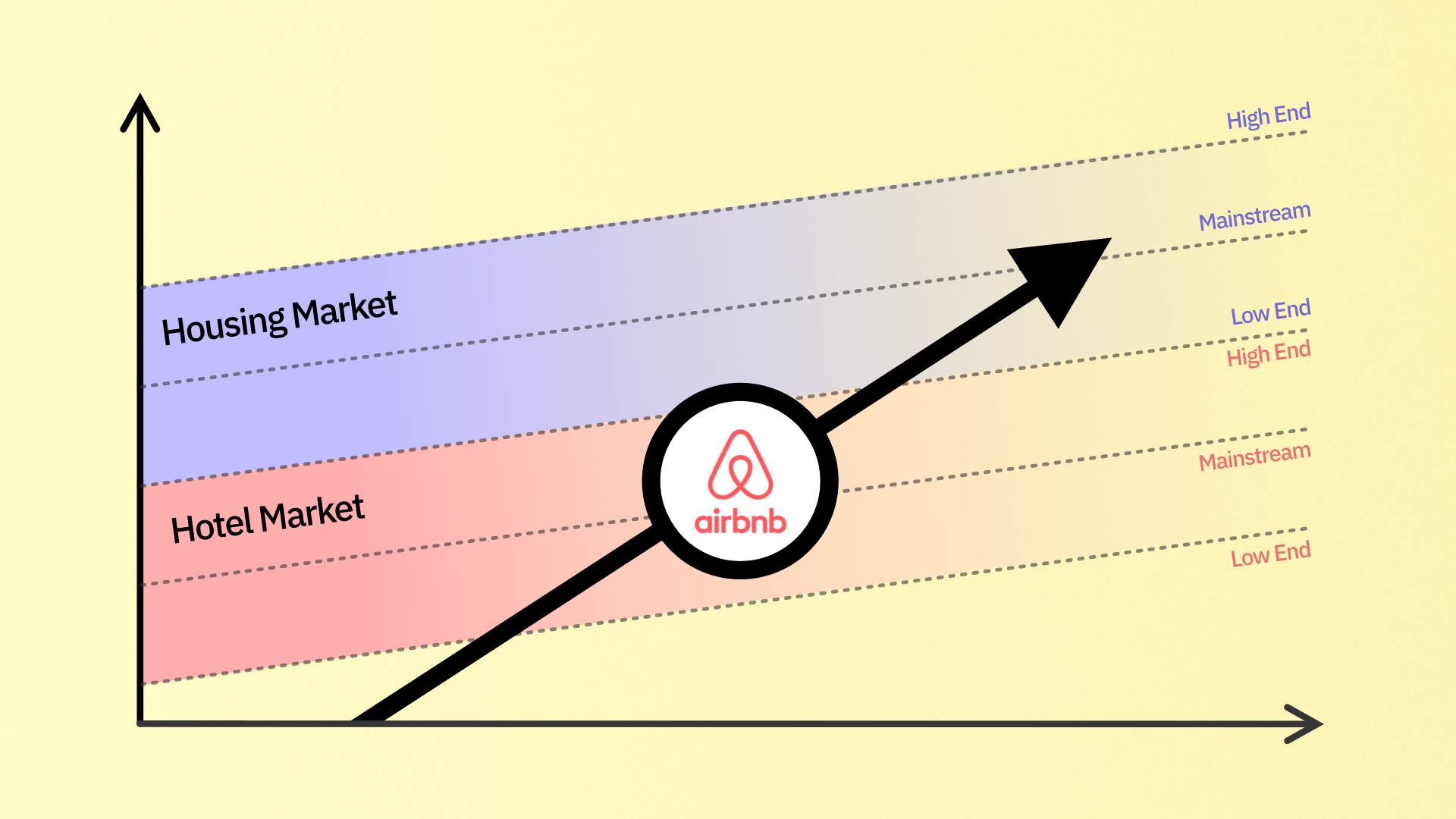

I used Airbnb's story to illustrate how disruption in one market ultimately affects other markets. In this case, Airbnb's initial foray into "hospitality" ends up impacting the "housing" market.

The article and a related post drew a lot of interesting comments on Linkedin. It also attracted some pushback and incredulity. The three main points of contention were:

- Airbnb will never be big enough to make a real impact on the overall rental market;

- Airbnb is actually disrupting the smaller and less important medium-stay or "serviced apartment" market rather than the residential market; and

- No one will ever be willing to pay a premium in order to book a longer stay via Airbnb instead of a traditional leasing or sublet process.

Let's address all three of these points. We'll start with the third one: Tens of thousands of people are already using Airbnb to book apartments for three or more months. For whatever reason, they are willing to pay a premium to book these apartments through Airbnb. What is the reason? That's a topic for a whole article. Still, the short answer is that Airbnb is simply more convenient — it has a friendly UX, it's a familiar brand, it allows you to pay with a credit card, and it provides some guarantees that mitigate whatever concerns you may have.

As Ben Thompson once told Tyler Cowen:

"The reality is — particularly when it comes to consumer products — is that in the long run, convenience always wins."

The housing market has other examples of customers paying a premium for something they can easily do on their own or find elsewhere. Consider the co-living market. Companies like Common Living charge a premium for letting you share an apartment with strangers. Can't people find a roommate on their own? Can't they coordinate and sign a lease together? Can they figure out who should buy the dish soap and split the cost of toilet paper?

Yes, they can! But it's more convenient to pay Common to do it for them. Common also offers specific services that make the process less daunting. If a customer is unhappy, Common allows them to switch to any other apartment within its portfolio — without breaking the lease. This makes it much easier to commit to an apartment full of people you don't know. Worst case — you can easily move into another furnished room elsewhere. Convenience!

And the best part is that customers are willing to pay a premium even though they hardly ever exercise the option to move. As Common's Founder, Brad Hargreaves, pointed out in an earlier talk, the ability to switch apartments is one of Common's most beloved features and a key driver of user decisions; at the same time, people rarely switch. But the fact that the option is there makes it easier for them to lease an apartment online, sight unseen, with people they've never met. Convenience! (also — Brad has an excellent new newsletter about emerging housing business models )

Beyond the premium, Common is also a great example of how customers are willing to commit to a long-term stay in the same way they book an Airbnb. A large percentage of Common customers sign leases online, sometimes before they even visit the city, let alone the apartment itself.

Now, let's address the second pushback: Airbnb is only disrupting the smaller and less important medium-stay or "serviced apartment" market rather than the residential market.

This is true. But it misses a huge point. Yes, the main people who use Airbnb to book an apartment on Airbnb are likely to stay only for several months (rather than years). But at the same time, the market for monthly and flexible stays is becoming a much bigger part of the overall housing market.

We've seen the same thing happen with offices. WeWork started by targeting the "serviced office" market, which was a tiny and uninteresting niche. But over time, furnished offices on flexible leases grew in popularity and now consist of 10-30% of the supply in key office markets across the world. It turns out that customers are willing to pay a premium for flexibility and convenience. WeWork didn't take over the "Serviced office" market; it helped make that market much bigger than it has ever been.

The same thing is now happening in the housing market. Airbnb is seeing massive growth in multi-month bookings because there is a growing demand for such bookings. Airbnb is not driving traditional services apartments out of business — it is growing the market for so-called serviced apartments.

And because the rental market is so large, you can build a giant business by dominating a sizable niche. For reference, there are about 50 million residential rental units in the US. If we assume the average rent is around $1,500, this means Americans spend $75 billion on rent each month — or nearly one trillion each year. For comparison, the US hotel market generates about $250 billion in revenue annually. And that figure includes hotel-based restaurants, conference centers, and other services.

Airbnb can build a giant business even if it doesn't control or dominate the housing market. This brings me to the third pushback: Airbnb will never be big enough to impact the overall rental market.

WeWork offers a great example of why that's not true. When WeWork emerged, most landlords thought it was an irrelevant joke. Then, they thought it was only relevant for freelancers and small companies. When they saw that WeWork also attracts some large corporate clients, they assumed that those customers would only go to WeWork for short-term leases and temporary solutions. Even when corporate tenants started paying WeWork a premium for multi-year leases on large spaces, landlords still didn't think this had anything to do with the "real" office market. "Yes," landlords told themselves, "some tenants want flexibility and furniture and apps and community... but most tenants will always opt for the empty boxes that we offer."

WeWork never took over the office market. Even at its peak, it was a tiny drop in a big ocean. But it did have an oversized share of the markets and tenants that matter. More importantly, the processes and services that WeWork introduced gradually became standard. Today, office tenants don't pay a premium for some flexibility, a good app, on-demand meeting rooms, community management, and access to furnished swing spaces. These things are now table stakes in many markets. It's no longer about paying a premium. Many large tenants won't even consider leasing space in a building that doesn't offer WeWork-like tech, flexibility, build-outs, community, and amenities.

The office and housing markets have more in common than people realize. They are both reshuffled by remote work and economic uncertainty. The housing leasing market is due for a revolution. Not because everyone is about to become a digital nomad, but because everyone has a life — and current apartments and leases are often at odds with how people live.

Consider my own life: Over the past seven years, I went from living alone in Beijing to living alone in New York. In between, I spent several months in Tokyo, Phnom Phen, and Tel Aviv. A year after renting an apartment in New York, I moved in with my fiancee in Brooklyn. Then we had a kid and needed more space. Then we wanted to spend more time with my recently-widowed mother-in-law during an isolating pandemic. Then we had another kid. Then... you get the idea.

Even for a boring middle-class dad like me, circumstances change in ways that a fixed lease cannot accommodate. And each set of circumstances is a relatively large market that a new housing brand can target (in the same way that Common caters to people looking to share a place in a new city). Combined, these multiple sets of circumstances are a massive market that Airbnb is now targeting — the market for flexible housing.

Even if it never takes over the housing market, Airbnb will change it forever. Its booking workflows, reviews, profiles, various services, and customer guarantees will gradually become standard — even for traditional long-term leases.

I'll talk more about this in tomorrow's webinar. It is free and open to the public. Click here to register.

Can't make it to the live session? Register, and we'll email you the recording.

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.