A History of Helplessness

I hope you'll forgive me for drawing your sympathy to one dead soldier. I know there are many others who deserve it.

I am overwhelmed. There is really too much going on at the moment. I am worried about my brothers and sisters in Israel who are under attack, and I am concerned about the Israeli government's lack of a positive vision on how to ensure that both Israelis and Palestinians can one day live in peace. The horrific images of Hamas's massacre and the ensuing Israeli response are heartbreaking.

I have cried each of the past thirty days. There is an old Israeli song called "The Winter of '73," in which children born around the Yom Kippur War confront their parents. The parents promised their children peace. They promised that by the time the children were grown, fighting would no longer be necessary. In the song, the grown children admonish their parents for failing to deliver that promise. You can find the lyrics here.

"The Winter of 73," performed by orphans of the Yom Kippur War, 50 years later.

My older sister, Dana, was born in February 1973, eight months before that war. My father was a military man, but he had already retired from fighting, or so he thought. Twenty-five years old and without even a high school diploma, he was appointed to teach history in a military academy in Jerusalem. This was a step towards becoming a civilian and spending more time with my mother and sister at home. In parallel, he planned to start a prep course for a degree in Psychology.

My mother, only 22 at the time, was delighted. She took a break from her physiotherapy studies to move with him to Jerusalem. She had met my father four years earlier when the whole country was still reeling — euphoric — from the great victory of the Six-Day War. She immediately fell for the young, handsome officer in an open-roof military Jeep. He reminded her of her father, a former officer in the Red Army who fought the Nazis and loved talking about the convertible he used to drive before the war took everything and everyone he had.

My father, an immigrant who spent his childhood in orphanages, was struck by the beautiful "sabra" girl, the first one to decline his invitation to visit the officers' barracks before going on a date.

Here they were, a young couple in Jerusalem with a little red-haired baby and wonderful plans. On Saturday morning, October 6, 1973, a Skyhawk fighter jet circled above Jerusalem. It was a signal for Israel's reserve pilots to head to their bases immediately. At 10 a.m., a friend called my dad and told him that war might break out. My father, still formally assigned to the Education Corps, got in his private car and headed north to join his former brigade.

Three days later, my mother got a call from a hospital up north. "Your husband is here; please come over." "I was so happy," my mother told me many years later. "I knew that he was alive and that, for him, the war was over. I didn't care what state he was in; I was happy he was alive." And he was.

My father's armored vehicle was hit by a missile during one of the battles against the invading Syrian army in the Golan Heights. The most senior officer in the vehicle died from the explosion; my father was hurt in his side and back. He was bleeding badly, but a group of brave rescuers who were there in response to a different incident managed to get him to a hospital in time.

Decades later, after I was born and was already a teenager, pieces of shrapnel would still occasionally come out of my father's skin. Many of his fellow officers were dead, and the army was devastated. Becoming a teacher? A psychologist? That dream would have to wait. My father stepped up to fill one of the many roles that were now vacant. Twenty years would pass until he finally left the army.

That song about the winter of 1973 was written about my parents and their friends. I used to feel angry at them whenever I heard it, angry at their failure to deliver on that promise. Angry that I had to go to the army and fight and deal with all the same crap.

These days, when I hear this song, I only feel angry at myself. Angry and ashamed. Now, I am the parent who failed. I assumed someone would bring peace. Or, worse, I assumed that peace might be too much to hope for and that it's possible to focus on other things.

There is plenty to cry about these days. The dead children are on both sides. The innocent civilians. The dashed hopes and betrayal of allies. The antisemitism.

But to me, nothing is more sad than dead Israeli soldiers. I almost feel like I should apologize for this sentiment. Israeli soldiers? Aren't they the ones least worthy of sympathy? They are the ones with the power, with the agency, with the intentions that keep the conflict in motion.

Or are they? Whatever your thoughts about Israel or the Palestinians, please bear with me.

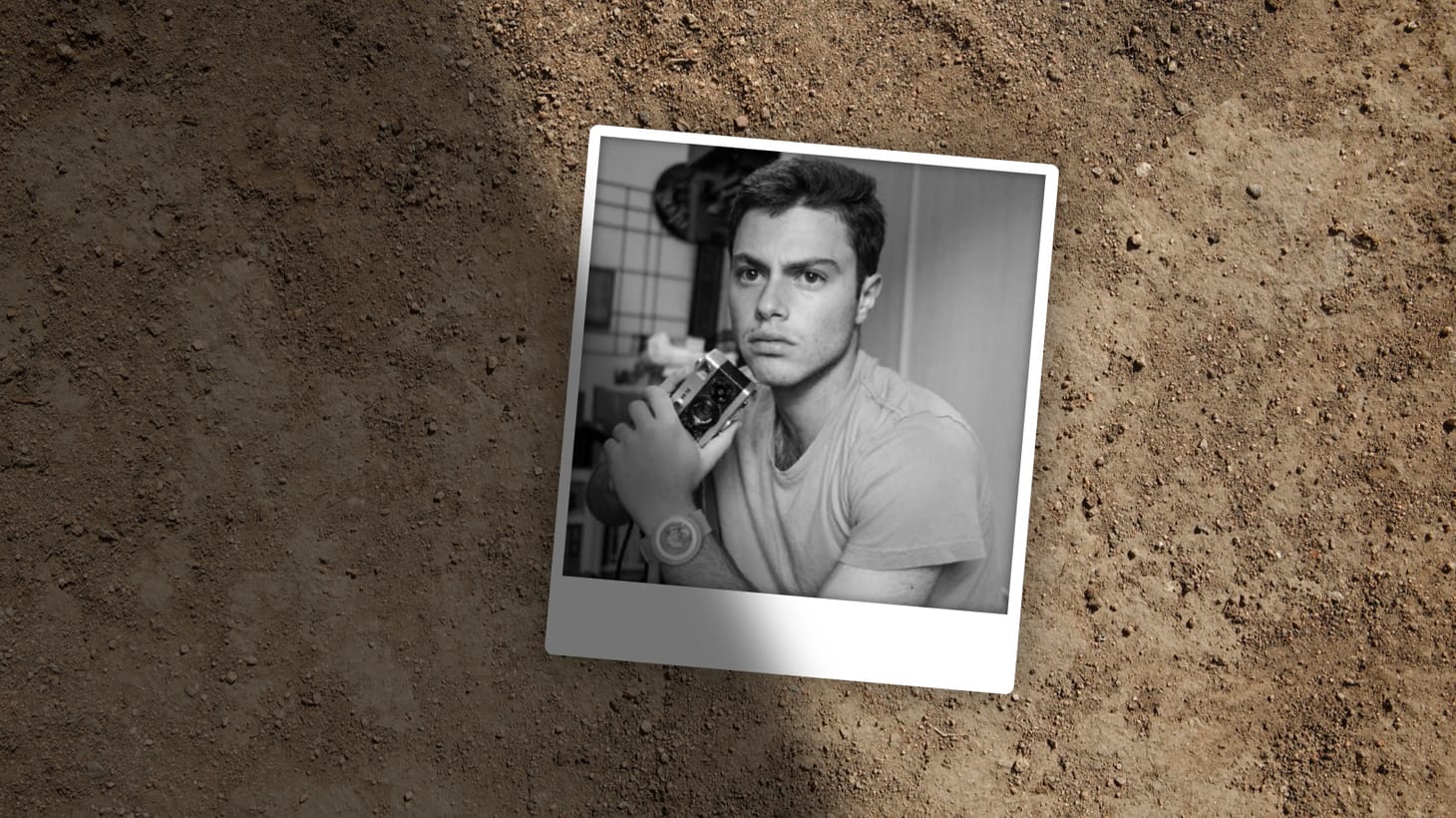

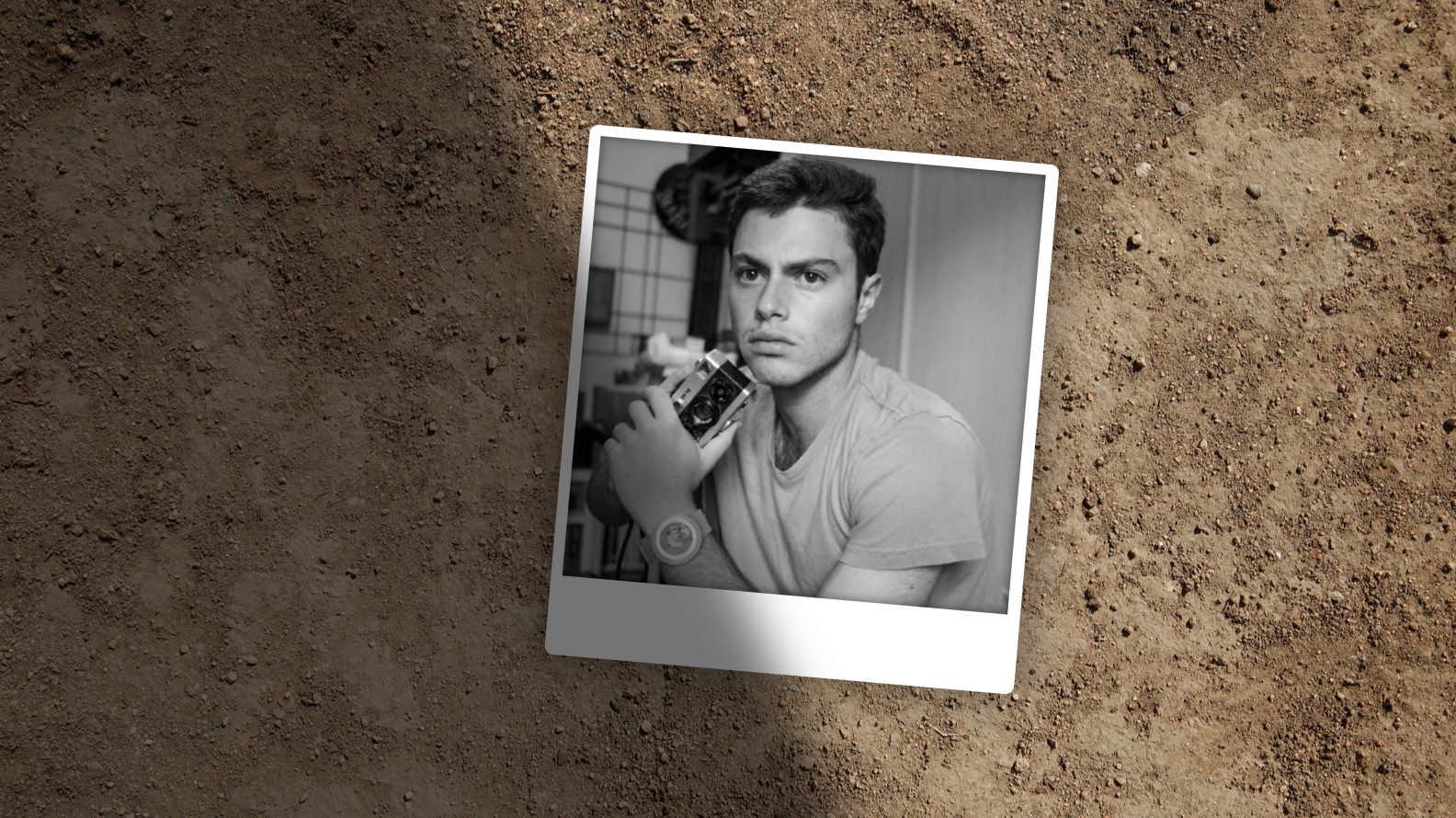

Lavi Lipshitz was twenty. As a teenager, he worked as a photographer, often volunteering to document weddings and birthdays for families who could not afford to pay. He dreamt of becoming a filmmaker. When he turned 18, he was conflicted about joining the army to complete the compulsory service required of all Israelis. "I do not want to become a fighting animal," he told his dad. Still, he felt obligated to repay the debt he owed to his country — a country that cannot exist unless young people step up to defend it.

"How to Ask Her Out?" by Lavi Lipshitz

A few months into his service, he sat next to a young lady on a bench outside a military clinic. They were both waiting for an X-ray appointment. They chatted about cinema, photography, and life. A few days later, he sent her a video he made to invite her on a date. It was an homage to the American director Wes Anderson, an effort to inject some life into the situation he was in.

On October 7, Lavi was among the first to rush to Kibbutz Nahal Oz to fend off a hundred Hamas terrorists who entered the small agricultural community in order to kill and kidnap its inhabitants. Lavi and his fellows fought for twelve hours until all the terrorists were captured or dead. Nahal Oz was one of dozens of spots that were attacked in parallel. By the end of that day, more than 1,200 Israelis were killed — women, children, Jewish, Muslim, and Christian. And at least 239 were kidnapped.

Three weeks later, Lavi was killed in Gaza in the battle to bring back the hostages and dismantle Hamas. His Instagram account, @till_when_photo_diary, is still online, showing his unique perspective on military life. The handle alludes to a common refrain among young army regulars — "Till When" — asking the heavens how much longer before they complete their service and go on with their lives.

I cry for Lavi because he reminds me of my twenty-year-old self. I, too, was once an aspiring artist trapped in uniform, struggling to reconcile my values and inclinations with the debt I owed to those who gave their life so I could grow up in relative peace. When I was 20, I scribbled Rimbaud's "Life is Elsewhere" on the bathroom door of a god-forsaken outpost in Lebanon. I spent hours talking about cinema and photography on the radio with the girls at the nearest outpost. And when I had to shoot, I shot.

They say the most significant part of trauma is the feeling of helplessness. More than the pain itself, it's the memory of not being able to do anything to stop it that haunts you. Soldiers are not obvious victims. Armed and trained, they are far from helpless. But at the same time, they are young, they have a debt of gratitude, they do as they are told, and they know too little. And years later, they, too, are haunted by their own helplessness.

Even at twenty, some are bright enough to know better or brave enough to do something about it. I wasn't, and nor was Lavi. And perhaps, there was no choice. Grappling with this question is a privilege reserved for those who made it out alive.

Rabbi Y.Y. Halberstam was the leader of a Chassidic community in Romania. He lost his wife and ten of his children in World War II. He survived multiple concentration camps and 'actions.' After the war, his disciples asked him about his experiences during the Holocaust. 'It could have been worse,' he said. 'We could have been the ones doing the killing.'

I hope you'll forgive me for drawing your sympathy to one dead soldier. I know there are many others who deserve it.

Thank you for reading.

P.S. — If you haven't done so already, please check out the Old New Fellowship, my new initiative to accelerate peace in the Middle East. 🕊️

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.