A Faster Office

Distributed work is a natural evolution of the office itself. To remain attractive, physical offices should stop thinking about productivity.

The audio version is available below and on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and beyond.

In the 1960s, the world's leading architect thought skyscrapers would make humans work less. In The City of Tomorrow and Its Planning, Le Corbusier writes:

"The city which can achieve speed will achieve success... Work today is more intense and is carried on at a quicker rate... The more rapidly this intercommunication can be made, the more business will be expedited. It is likely, therefore, that the working day in the sky-scaper will be a shorter one... the working day may finish soon after midday. The city will empty as though by a deep breath."

Put differently, Le Corbusier predicted that once information can flow faster, urban offices will be empty half of the time. He was right, but not in the way he intended.

Today, many urban offices are indeed half-empty, and information does flow faster. But it doesn't flow in the elevators and pneumatic tubes of the skyscraper; it flows on the internet.

Le Corbusier's prediction is a classic example of static, first-order thinking. It assumes that when one thing changes, everything else will remain the same. In reality, the ability to process more information led to the processing of even more information (and not finishing work "soon after midday").

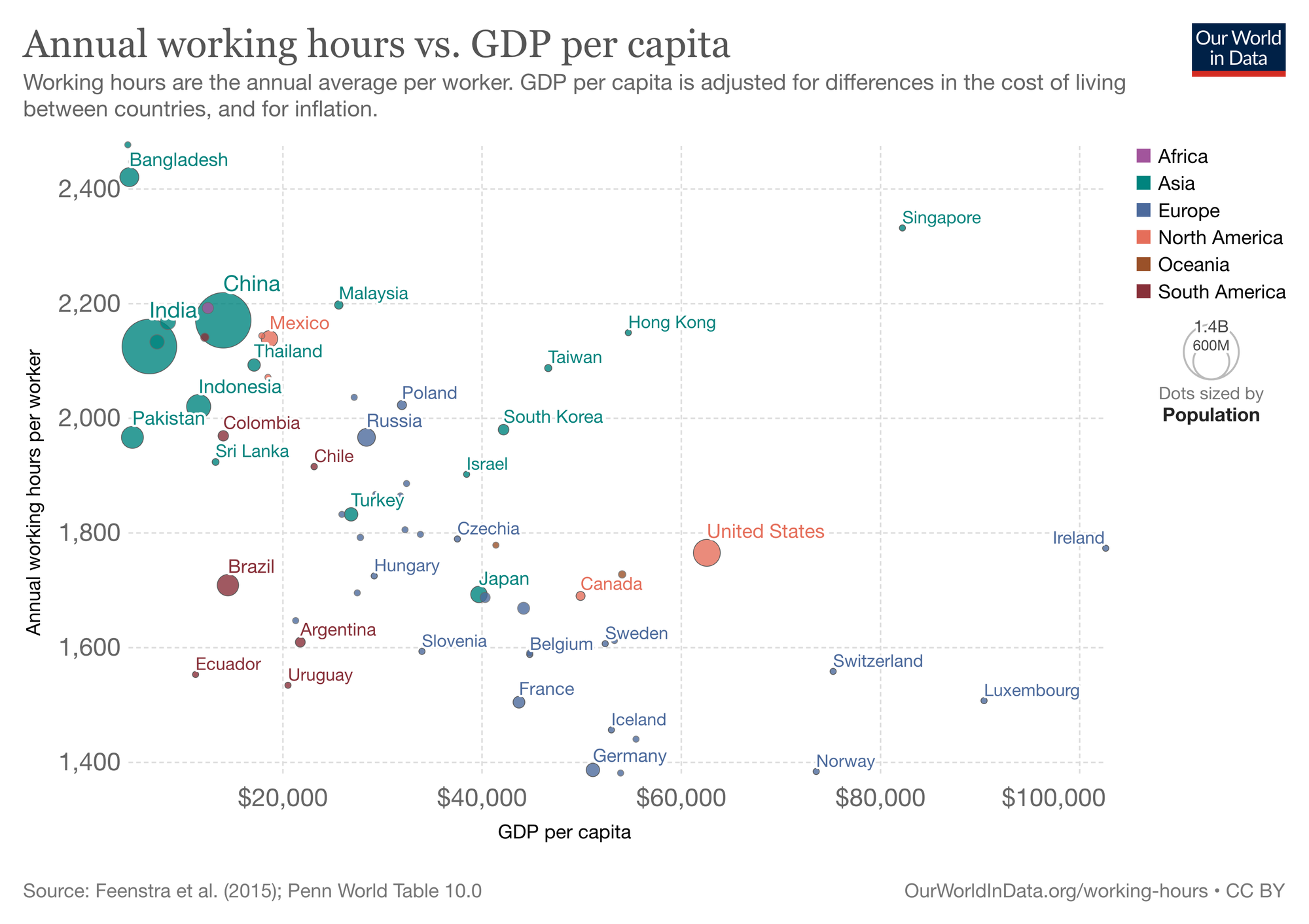

To be fair, people's working hours did decrease over the past century. But they decreased much faster before Le Corbusier's book and before offices became the predominant way to work. As countries become wealthier, working hours tend to decrease (unless you're in Singapore):

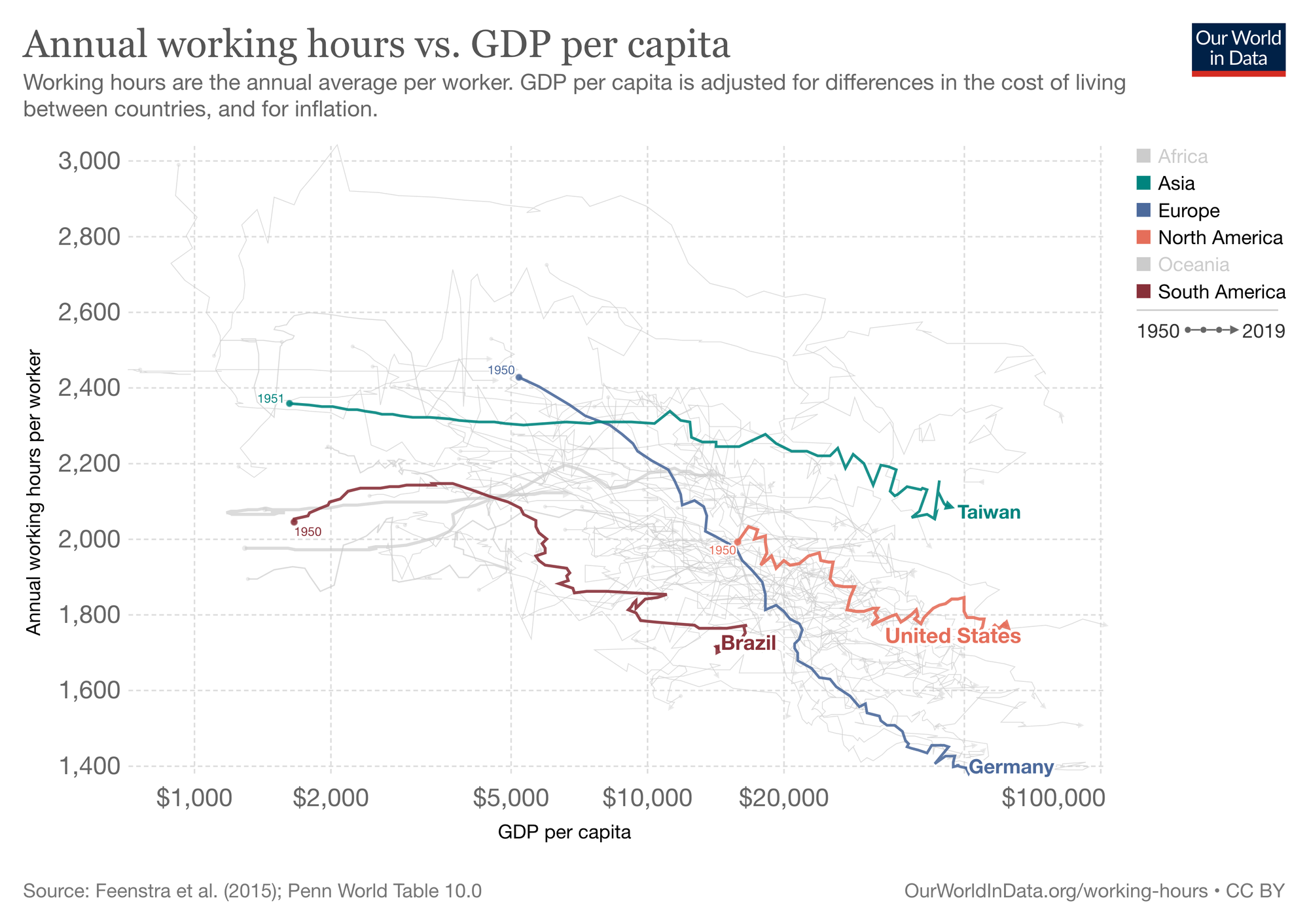

The effect is clearer over time:

Le Corbusier got one thing right: Productivity is a function of speed. The more information that can be transmitted and processed, the more likely it is to produce a valuable idea. This is more true than ever, even though it seems like most information is frivolous noise.

If the purpose of the office (and the city) is to increase the speed of communication, it makes sense for them to be replaced by solutions that enable even more speed. Such solutions can include remote work or offices that require shorter commutes.

It’s not the office, it’s the commute.

— Dror Poleg (@drorpoleg) August 19, 2020

Some people saw that coming. Writing in 1900, H. G. Wells predicted that the growing densification of cities will soon reverse:

"These great cities are no permanent maelstroms. These new [technological] forces, at present, still so potently centripetal in their influence, bring with them, nevertheless, the distinct promise of a centrifugal application that may be finally equal to the complete reduction of all our present congestions. The limit of the pre-railway city was the limit of man and horse. But already that limit has been exceeded, and each day brings us nearer to the time when it will be thrust outward in every direction with an effect of enormous relief."

Wells was right, even though it took another 60 years for the "centrifugal" trend to become dominant. Cities and their labor markets expanded outwards into the suburbs and became both larger and less dense. All this was enabled by technology that made it cheaper and easier for people to commute and communicate across larger distances.

I dive deeper into this process in my book. Last week, I chatted with Dr. Judy Stephenson about the organization of pre-industrial cities (recording here). And next week, I'm hosting a live chat with Alain Bertaud about the spatial evolution of cities (sign up for free here).

But let's return to the office and its role.

A few years before Le Corbusier made his prediction, Henry Ford's motor company was among the first to institute a 40-hour workweek. That meant reducing the workweek from 6 to 5 days and limiting daily work to 8 hours. Ford thought that more leisure would increase productivity and stimulate the economy.

"It is high time to rid ourselves of the notion that leisure for workmen is either lost time or a class privilege... People who have more leisure must have more clothes, they eat a greater variety of food... They require more transportation in vehicles."

At first, the policy only applied to factory workers. But a few months later, Ford decided to implement it at the corporate office. The change coincided with a change in For's product strategy — moving away from the frugal and functional Model T and introducing of the more stylish and customizable Model A.

Initially, the Model T was uniquely affordable. But in the 1920s, there were many competing models, and the T was a commodity. The new Model A was aimed at people who wanted to express themselves through consumption rather than get from point A to point B. It was a hit.

Ford is famous for saying that if he'd asked his customers what they wanted, they would have asked for a faster horse. There's no evidence he actually said that, but the point remains. Relying on your customers' imagination will only get you this far. The next big thing is hardly ever an extrapolation of the last thing.

That's what happened to offices.

What can be done? I am still working on the comprehensive answer to this question. But another proponent of Ford offers a hint. Steve Jobs

“People don't know what they want until you show it to them. That's why I never rely on market research. Our task it to read things that aren't yet on the page.”

How can you read things that aren't yet on the page? Well, one way to secure advance access to insights from a book that's still being written. The second best option is to contemplate Jobs's message on your own. Don't ask people what they want. Delight them with something they didn't even know they wanted.

Have a great weekend! Join me next week for a conversation with Alain Bertaud.

Best,

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.