Arabian Dreams

Thoughts on what makes places attractive, on urbanism's capacity to foster peace and prosperity, and on the most complicated "real estate" conflict in the world — following my first visit to Saudi Arabia.

🎧 The audio version of this article is available on Spotify, Apple Music, and beyond.

"When the bees feel the queen is weak or unwell, they produce a new queen. The worker bees feed royal jelly to larvae in several cells to ensure that at least one new queen would hatch. Once the first new queen hatches, she or the worker bees sting the other cells to eliminate other potential queens." The camels were running outside, and I was getting a lesson about bees from James Dearsley, who sat next to me on the ride to CityScape Global on the outskirts of Riyadh. "Sometimes, a new queen hatches, but the old queen remains alive." In such a situation, the old queen either leaves with a swarm to form a new hive, or the two queens fight to the death. The stronger, more agile queen wins, killing the other. This ensures the colony has the most fit queen to lead it.

It was my first visit to Saudi Arabia. I landed in Jeddah two days earlier, on a Friday morning. Friday is the local day of rest, the Muslim Sabbath. The airport is named after King Abdulaziz Al Saud, who founded Saudi Arabia in 1932. Most people know the region's history through Lawrence of Arabia, the film by David Lean. In that story, the Arabs are represented by Faisal of Mecca, whose Hashemite tribe helped the British kick the Ottoman Empire out of Arabia and Syria during World War I.

In return for their support, the Brits agreed to grant the Hashemites an independent Arab state in the vast area spanning Arabia and current-day Syria, Lebanon, Israel-Palestine, Jordan, and Iraq. The Hashemites already governed (and protected) Mecca and Medina, Islam's two holiest cities, under the auspices of multiple empires for a thousand years. The deal with Britain was meant to expand their domain and give them formal international recognition.

But the Brits also made other promises to other people. In a secret agreement signed during World War I, they promised France large chunks of the same region that the Hashemites understood to be theirs. A year later, Britain also expressed formal support for a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, which was then controlled by the Ottoman Empire.

Incredibly, the Hashemite Arabs managed to reach an agreement with the Jews to carve out some land for Jewish settlement in what is currently Israel, contingent on the fulfillment of the British promises to the Hashemites. The agreement, facilitated by the legendary T.E. Lawrence, mentioned the "racial kinship and ancient bonds existing between the Arabs and the Jewish people" and acknowledged that "the surest means of working out the consummation of their natural aspirations is through the closest possible collaboration in the development of the Arab State and Palestine."

But while Jews and Arabs may have reached an agreement, the French were a different story. They were unwilling to give up the areas promised during the war and kicked Faisal out of Damascus. As a consolation prize, Faisal was given the Kingdom of Iraq, his brother Abdullah received the Kingdom of Transjordam (now Jordan), and his father Hussein ruled the Kingdom of Hejaz in Arabia. The French took Syria and Lebanon, the British took Palestine and retained direct and indirect control of other parts of the region. And the Jews did not receive their promised land.

Thus, the end of World War I left the Middle East with what Historian David Fromkin called "a peace to end all peace." The region was divided arbitrarily and casually by Britain and France. As Churchill put it, he created new countries "one Sunday afternoon," probably while having a Whiskey. The result was a series of new countries filled with tribes and nationalist movements who did not wish to live together within borders that didn't make sense. Since the Brits reneged on their promise to the Hashemites, Faisal's agreement with the Jews was also nullified. The Brits, for their part, also failed to materialize the 1917 plan for a Jewish national home in Palestine, leaving the Jews to their fate. This led to intensifying conflicts between Jews and Arabs in British-controlled Palestine and culminated in the systematic murder of 6 million Jews in Europe and North Africa in the 1940s.

The Hashemites didn't just end up with less than they were promised; they also lost more than they thought possible. In 1925, they lost Mecca and Medina after a battle with the Sauds, a family from northeastern Arabia. By 1932, Abdulaziz Al Saud consolidated several territories and formed the new Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Six years later, the California Arabian Standard Oil Company (later renamed ARAMCO) discovered a massive oil reserve in Saudi Arabia's eastern region.

In 1947, the U.N. adopted a plan to partition Palestine into two independent states, one for the Jews and one for the Arabs, with Jerusalem under international control. The Palestinian Arabs rejected the plan. The Jews accepted it and established the State of Israel in May 1948. The Saudis sent a small force to fight alongside Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq to nip the new country in the bud.

And the rest is history. The purpose of the recap above was to point out that things could have turned out differently — that the Middle East was shaped by (bad) decisions that could have been otherwise. And that many of these decisions were made by outsiders from England, France, and beyond.

Back to September 2023. I was standing in line for border control at King Abdulaziz airport. A Saudi officer took my passport and swiped it into the reader. He then swiped again and again. It didn't seem to work. "Dror?" he looked up at me. Yes, I answered. He called one of his colleagues. They discussed something and then called another supervisor. It was a new passport; perhaps the biometric data strip did not scan. "Do you have a visa?" Luckily, I had it printed out. They had a look. Leafed through the passport. Discussed some more. Then, the first officer scribbled something by hand and stamped one of the back pages. "Welcome!"

I kept my cool throughout this ordeal. I felt determined. I've come all this way. There is no chance you are not letting me in to see this place! I've been waiting for this trip for months. Years, actually. I've been invited several times before, but it didn't work out. And while I was born just a little to the north of Saudi Arabia, it was one of those places I was least likely to visit. I left the region in 2001, living in Australia, China, England, and finally settling in the U.S. But I remain connected to it and invested in its development. And like many of my generation, I always dream of peace.

Perhaps I am lucky, but the worst day of my life is a national rather than a personal event. When I was 15, in 1995, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was murdered. He was murdered because he was trying to negotiate a peace agreement with Israel's Arab neighbors. He managed to conclude an agreement with Jordan and was killed while trying to finalize a deal with the Palestinians. Perhaps he would have failed anyway, but at least he tried. His efforts filled the region with the hope of shared prosperity, an inkling of that "racial kinship and ancient bonds existing between the Arabs and the Jewish people" mentioned in that old agreement from the end of World War I.

Rabin's death represented the death of the peace dream. It also represented a break in the idea of Israel itself. Jews thought that in their country, something like this could never happen — that a Jew would murder another Jew for political reasons, that a religious zealot would kill a war hero for trying to bring peace. It was heartbreaking, and just thinking about it brings me to tears.

Rabin's murder also signified Israel's cultural assimilation in the Middle East. The country was founded by secular, socialist Jews who wanted to build a model society. But like its Arab neighbors, Israel was being overtaken by fundamentalist forces that had a far darker vision in mind. To add insult to injury, a few months after the murder, Benjamin Netanyahu, who incited against Rabin and fanned the flames of hate, was elected prime minister.

I felt like I lost my home, like my country no longer existed. And indeed, I soon left it and never returned.

Why am I telling you all this? Frankly, I am not sure. This whole Saudi adventure brings it out of me. My point is that I take peace in the Middle East personally. Visiting an Arab country — and such an important one — is a very special event. And while some look at the Middle East as some faraway place, for me, it is home. It is an unfinished business and an old, interrupted dream. Before (and after) my trip, some people asked me if I had any moral qualms about visiting Saudi Arabia — with its spotty human rights records and discrimination against women.

On the one hand, this question seems irrelevant to me. Of course, I do not condone the country's policies, but I also do not have the privilege to lecture it from afar. I was born and raised in the Middle East, I have fought in the Middle East, and I have paid the price of war. Would I decline an opportunity to engage with Arab people in a peaceful manner? To talk to them about their plans, hopes, and aspirations? To share my ideas and thoughts with them? Of course not. I was eager to visit, engage, and see it with my own eyes. On the other hand, my actual ideas address the region's problems. More on that in a moment.

Anyway, here I was. Now in Riyadh after a 16-hour trip. I dropped my bags in the hotel and immediately set out. On the first day, I visited the Masmak Fortress and the Al Zel market and walked around their surrounding areas. In the Uber ride from my hotel, the driver asked whether I'd ever been to a Saudi home. When I said I hadn't, he dialed his mother and invited me over. I declined politely, which I now regret. Several other people invited me to visit their homes in the following days.

On the second day, I visited Kingdom Tower and the areas surrounding Al Murabba Palace and King Abdullah Park. The streets of Riyadh are mostly empty of pedestrians during the day, and most shops only open around 4 p.m. and remain open late into the night. The heat during the day and the night in September is spectacular, ranging from highs of 45 degrees Celsius to lows of around 28 (115 - 83 F). The air is dry, and breathing sometimes feels like someone is blowing a hair dryer up your nose.

To counter the heat, and perhaps as an old habit from my retail development days, I spent a lot of time in shopping malls, including Al Nakheel Mall, Riyadh Park, Riyadh Front, Park Avenue Mall, and Kingdom Centre. Riyadh's mall has every brand imaginable, including relatively niche brands (West Elm) and food chains that can't even be found in Manhattan (Little Caesars Pizza). Most have signage in both Arabic and English, and a few have a localized version of their logo — see H&M in the lower-left corner below.

The malls stand in contrast to the rest of the city. Riyadh was less developed than I expected. It was clean, it felt safe, and the roads were good. But the overall housing and retail stock was modest and reminded me of China twenty years ago and even more so of Israel 35-40 years ago. Solid, functional, but modest. There are also a handful of skyscrapers. Alongside the malls, the universities were the other buildings that seemed most spectacular. Several large, modern campuses around the city are both beautiful and modern. And the soon-to-open Riyadh Metro lines and trains are visible in different parts of the city.

Riyadh was more open and more conservative than I had expected. It was easy to get around, and the people I spoke to seemed excited to chat with a visitor. There were plenty of women wearing niqābs and hijabs, but also many that didn't. Women have limited rights in Saudi Arabia. Over the past two decades, particularly since 2018, they have enjoyed many new freedoms, including the right to vote and get elected in municipal elections, drive, travel overseas, and perform different actions without requiring approval from their husband or "guardians."

While women enjoy many more formal rights, they may still be restricted and ostracized by their families and communities. Some argue that reforms mean the state will no longer stop women from doing things their clan or family allow, but that reforms don't go far enough to protect and empower women who are restricted.

It is worth noting that most of the legal restrictions on women — both those intact and already canceled — only date back to the country's 1979 "Islamic revival." Back then, the government enforced new limits on women in response to violent acts and protests by religious fundamentalists who threatened to overthrow the ruling family. The Islamic resurgence in Saudi Arabia and Iran following 1979 is outlined in Kim Ghattas's excellent book Black Wave. Before 1979, Saudi women were allowed to drive, study, and work (more) freely and were not legally required to wear a veil in public or seek approval from guardians for travel and access to services.

Much progress has been made over the past few years, and MBS seems earnest in his desire to reform the country. While legal changes are welcome, the real challenge is changing local culture and managing the mental "evolution" of many of the country's conservative men. Islam maintains a strong and constant presence everywhere in Riyadh. One often hears the calls of the muezzin from nearby mosques, as well as from the sound system at the mall and apps on people's phones. Prayer rooms are common, with multiples in every building or mall floor. Many public bathrooms include a special section for ablutions or wudhu — the ritual washing of the head, arms, and feet before prayer. Consuming or carrying alcohol is forbidden everywhere, even in private. The general vibe felt much more religious and conservative than in neighboring Dubai. I expect the contrast is even more pronounced in the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. Locals told me that Jeddah, located along the shores of the Red Sea, feels more open and hedonistic.

I spent my third and fourth days at the CityScape Global conference. It was located in a massive convention center about 50 miles north of the city. A few miles out, all the buildings recede, and one is surrounded by nothing but desert. Occasional camel herds appear outside the window.

And finally, I arrived at the conference grounds. CityScape Global was, according to the organizers, the biggest event of its kind in the world, with 180,000 registered visitors expected over four days. It was more a trade show than a conference, with most of the space dedicated to booths representing different projects and companies and several stages sprinkled across three large halls. There were booths representing all the major new cities and projects in the country.

The pièce de résistance was a giant model of The Line, a futuristic city that Saudis are planning/building in the country's west — see illustration below and cross-section above. The Line is located in Neom, an area the size of New Jersey (or Belgium), designed to attract international talent and tourists. The Line and Neom are often used interchangeably, but the latter will include other cities/communities with different characteristics, including one in the mountains where people are expected to ski.

Beyond the radical architecture, the most interesting aspect of Neom might operate another different legal regime, allowing the Saudis to experiment with some social and economic reforms — and to appeal to foreigners who like to drink alcohol and dress or party in ways that would not be appropriate elsewhere in the kingdom. I wrote "might" because government officials have denied reports about Neom's experimental regulations, but they also seem to be under consideration.

Neom is the pet project of Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS). It is meant to showcase the urban technologies of the future and allow people to have whatever they need within 5 minutes of their home, travel from side to side of the city on public transport in 20 minutes or less, and have "zero cars and zero carbon emissions." The residential and commercial areas are designed to preserve 90% of the area's natural environment.

Beyond the beautiful desert, mountains, beaches, and new residents, the area designated for Neom already has an existing population, most notably the Howeitat tribe. There have been reports of tensions, arrests, and even "planned executions" of locals who oppose the new development or the process by which it proceeds.

(For those of you interested in Trivia: The Howeitat are the tribe of Auda Abu Tayi who fought alongside T.E. Lawrence and Faisal of Mecca's troops in the battle of Aqaba. The battle facilitated the British conquest of Palestine and Syria and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Abu Tayi was immortalized by Anthony Quinn in the film Lawrence of Arabia.)

While it is common for new projects to face strong resistance all over the world, the opacity of Saudi Arabia's system makes it hard to know what is actually going on and raises significant concerns.

Which brings me to my keynote presentations. The first one focused on the future of work and offices, covering material my regular readers are familiar with. The second one was more specific, focusing on Saudi Arabia's opportunity to attract talent, tourists, and international companies. I started with my general thesis about the world becoming more open — people can live and work in more places, and top talent can access the best jobs from anywhere. This creates an opportunity for new cities and regions.

I sought to explore a simple but giant question: What makes a place attractive to people who can live anywhere?

The first part of the answer focuses on each place's functional aspects, as I have argued elsewhere:

"in a world of consumer choice, locations must think like consumer products. One way to win is to double down on what only the biggest cities can offer—walkable streets, car-free transportation, and cultural and intellectual diversity. But smaller cities can emphasize shorter commutes, ample parking, proximity to nature, better schools, and lower taxes."

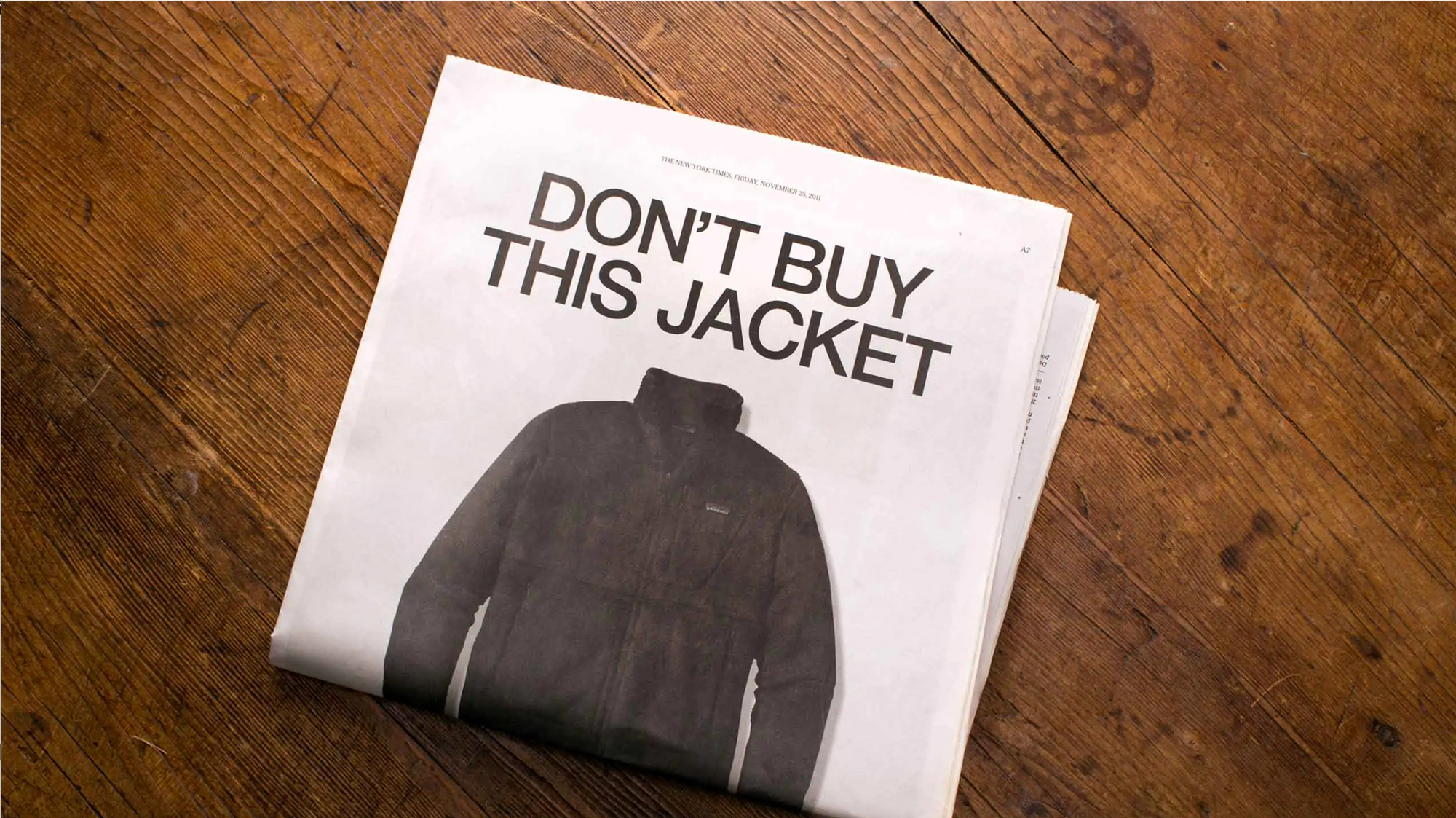

But the second part is more important. The best consumer brands go beyond addressing their customers' functional needs and preferences. They appeal to the customer's values and aspirations. The highest level is making the customer feel like they're active contributors to something big and meaningful — to feel like they are making the world better by buying your product.

Patagonia's 2011 advertising campaign epitomizes this approach. It tells potential customers not to buy its products. It highlights the company's focus on making products that are made responsibly and do not require constant replacement. And even when you feel like something new, Patagonia will help you recycle or resell your product and get something else in return — even years after purchase. By buying Patagonia, the ad implies, you are not just limiting your harm but being proactively good.

Cities and regions need to think along the same lines. They need to seek meaning and tap into the values and aspirations of their potential customers (residents or tourists). They need to come up with a big idea that people would want to contribute to. They need to come up with a story and invite people to be a part of it.

What could this story be for Saudi Arabia and the Middle East? What is that one thing that people can aspire to contribute to?

I offered a possible answer: Peace. If people feel that their presence—their work or even their vacation—contributes to bringing stability and peace to the Middle East, they will spend more time here.

But peace is not just a word or a slogan. The massive investment in the region has to be tied to real change—economic opportunities for the tens of millions of young men and women, a just solution for all the refugees in the region (the Palestinians, in particular), and infrastructure and education focused on regular people, not just the super-rich.

This was my final message, and even though it was just one presentation in a giant conference full of very distracted people, I was quite excited to share it. It might sound naive or abstract, but it can be translated into practical steps. Peace is good for business, and the massive investments planned in the region can go a long way to alleviate scale back and cool down the region's conflicts and flashpoints. That's a story everyone would love to be a part of. Let's write it. Let's build it.

Have a great weekend and a happy and sweet new year to those who celebrate!

Best,

P.S.

🎧 I chatted with Jim O'Shaughnessy on the relationship between A.I.P.S and remote work, how cities will change, the internet'sO'Shaughnessy role as a matching engine, and much more. Click here to listen.